Sayyida Hurra: The Ismaili Sulayhid Queen of Yemen

Abstract

This article explores the career of queen Sayyida Hurra, she was the political and religious leader of Sulayhid Yemen, which was an extremely rare occurrence and privilege for a woman in Fatimid times. Hurra was closely linked with the Ismaili daʿwa in Cairo, and rose up the ranks of the Fatimid daʿwa to receive the rank of hujja. Hurra was the first woman in the history of Ismailism to gain high rank in the Ismaili hierarchy, thus making this appointment a unique event. Daftary traces other events such as the Mustaʿli-Nizari split and looks at how Hurra dealt with these incidents and the implications for the Ismaili daʿwa.

The career of the queen Sayyida Hurra is a unique instance of its kind in the entire history of medieval Islam, for she exercised the political as well as religious leadership of Sulayhid Yemen; and in both these functions she was closely associated with the Ismaʿili Fatimid dynasty.

This article was originally published in Gavin R. G. Hambly ,ed., Women in the Medieval Islamic World: Power, Patronage and Piety and reprinted in The New Middle Ages, 6. New York: St .Martin’s Press, 1998, pp. 117-130. Reprinted with corrections, 1999

Introduction

Few women rose to positions of political prominence in the medieval dar al-Islam, and, perhaps with the major exception of Sayyida Hurra, none can be cited for having attained leadership in the religious domain. A host of diverse factors have accounted for a lack of active participation of women in the political and religious affairs of the Islamic world during the medieval and later times; and the associated complex issues are still being debated among scholars of different disciplines and among Muslims themselves. Be that as it may, there were occasional exceptions to this rule in the medieval dar al-Islam, indicating that opportunities did in principle exist for capable women to occupy positions of public prominence under special circumstances. This article briefly investigates the career and times of the foremost member of this select group, namely the queen Sayyida Hurra who, in a unique instance in the entire history of medieval Islam, combined in her person the political as well as the de facto religious leadership of Sulayhid Yemen; and in both these functions was closely associated with the Fatimid dynasty and the headquarters of the Ismaʿili daʿwa or mission centered at Cairo.

Education Policies

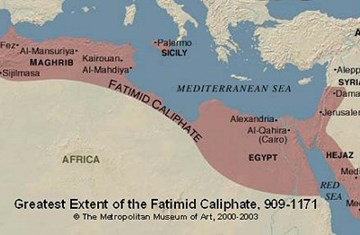

The Fatimids, who established their own Ismaʿili Shiʿi caliphate in rivalry with the Sunni ʿAbbasids, were renowned for their tolerance towards other religious communities, permitting meritorious non- Ismaʿili Muslims and even non-Muslims to occupy the position of vizier and other high offices in their state. As part of their general concern with education, the Fatimids also adopted unprecedented policies for the education of women. From early on in the reign of die founder of the dynasty, ʿAbd Allah ['Ubayd Allah) al-Mahdi (297-322/909-34), the Fatimids organized popular instruction for women.1 And from the time of al-Muʿizz (341- 65/953-75), who transferred the seat of the Fatimid State to Egypt and founded the city of Cairo, more formal instruction was developed for women, culminating in the majalis al-hikma [sessions of wisdom] on Ismaʿili doctrines. Al-Maqrizi (d. 845/1442),2 quoting al-Musabbihi (d. 420/ 1029) and other contemporary Fatimid chroniclers, has preserved valuable details on these lectures which were delivered regularly on a weekly basis under the direction of the Fatimid chief daʿi, the administrative head of the Fatimid Ismaʿili daʿwa organization. The entire program was also closely scrutinized by the Fatimid caliph-imam, the spiritual head of the daʿwa. The sessions, organized separately for women and men, were arranged in terms of systematic courses on different subjects and according to the participants' degree of learning. Large numbers of women and men were instructed in various locations. For women, there were sessions at the mosque of al-Azhar, while the Fatimid and other noble women received their lectures in a special hall at the Fatimid palace. As reported by Ibn al-Tuwayr (d. 617/1220), special education for women evidently continued under the Fatimids until the fall of their dynasty in 567/ 1171.3

Women in the Fatimid Dynasty

As a result of these educational policies and the generally tolerant attitudes of the Fatimids, there were many educated women in the Fatimid royal household and at least some among them who were also endowed with leadership qualities did manage to acquire political supremacy. In this regard, particular mention should be made of the shrewd Sitt al-Mulk, the sister of the Fatimid caliph imam al-Hakim (386-411/996-1021), who ruled efficiently as the virtual head of the Fatimid state in the capacity of regent during the first four years of the caliphate of al-Hakim's son and successor, al-Zahir, until her death in 415/1024. There was also al-Mustansir's mother, who although not brought up in Egypt did become a powerful regent during the first decade of her son's caliphate (427-87/1036-94); and subsequently, in 436/1044, all political power was openly seized and retained by her for a long period. It is significant to note that tile ascendancy of these women to political prominence was not challenged by the Fatimid establishment or the Ismaʿili daʿwa organization; and, in time, al-Mustansir not only acknowledged Sayyida Hurra's political leadership in Yemen but also accorded the Sulayhid queen special religious authority over the Ismaʿili communities of Yemen and Gujarat. It is indeed within this general Fatimid Ismaʿili milieu that the queen Sayyida's status and achievements can be better understood and evaluated in their historical context.

Sulayhid dynasty – early accounts

The earliest accounts of the Sulayhid dynasty, the queen Sayyida's career, and the contemporary Ismaʿili daʿwa in Yemen are contained in the historical work of Najm al-Din ʿUmara b. ʿAli al-Hakami 4 the Yemenite historian and poet who emigrated to Egypt and was executed in Cairo in 569/1174 for his involvement in a plot to restore the Fatimids to power. Ismaʿili historical writings on the Sulayhids and on the contemporary Ismaʿilis of Yemen are, as expected, rather meager. Our chief Ismaʿili authority here is again the Yemenite Idris 'Imad al Din (d. 872/1468), who as the nineteenth chief daʿi of the Tayyibi Ismaʿili community was well-informed about the earlier history of the Ismaʿili daʿwa. In the final, seventh volume of his comprehensive Ismaʿili history entitled ʿUyun al-akhbar, which is still in manuscript form, Idris has detailed accounts of the Sulayhids and the revitalization of the Ismaʿili daʿwa in Yemen under the queen Sayyida; here I have used a manuscript of this work from the collections of the Institute of Ismaili Studies Library.5 In modern times, the best scholarly accounts of the Sulayhids and the queen Sayyida as well as the early history of Ismaʿilism in Yemen have been produced by Husain F. al-Hamdani (1901-62), one of the pioneers of modern Ismaʿili studies who based his work on a valuable collection of Ismaʿili manuscripts preserved in his family. 6

Yemen

Yemen was one of the regions where the early Ismaʿili daʿwa achieved particular success. As a result of the activities of the daʿis Ibn Hawshab Mansur al-Yaman and ʿAli b. al-Fadl, the daʿwa was preached openly in Yemen already in 270/883; and by 293/905-06, when Ibn a-Fadl occupied Sanʿaʾ, almost all of Yemen was controlled by the Ismaʿilis. Later, the Ismaʿilis lost the bulk of their conquered territories to the Zaydi imams and other local dynasties of Yemen. With the death of Ibn Hawshab in 302/914 and the collapse of the Ismaʿili state in Yemen, the Ismaʿili daʿwa continued there in a dormant fashion for over a century. From this obscure period in the history of Yemenite Ismaʿilism, when the Yemenite daʿwa continued to receive much secret support from different tribes, especially the Band Hamdan, only the names of the Yemenite chief daʿis have been preserved. 7

Sulayman b. ʿAbd Allah al-Zawahi

By the time of the Fatimid caliph-imam al-Zahir (411-27/1021-36), when Yemen was ruled by the Zaydis, the Najahids, and other local dynasties, the leadership of the Yemenite daʿwa had come to be vested in the daʿi Sulayman b. ʿAbd Allah al-Zawahi, who was based in the mountainous region of Haraz. Sulayman chose as his successor ʿAli b. Muhammad al-Sulayhi, the son of the qadi of Haraz, and an important Hamdani chief from the clan of Yam who had been the daʿi's assistant. In 429/1038, the daʿi ʿAli b. Muhammad al-Sulayhi rose in Masar, a locality in Haraz where he had constructed fortifications, marking the foundation of the Ismaʿili Sulayhid dynasty. With much support from the Hamdani, Himyari and other Yemenite tribes. ʿAli b. Muhammad soon started his rapid conquest of Yemen, and by 455/1063, he had subjugated all of Yemen. Recognizing the suzerainty of the Fatimid caliph-imam, ʿAli chose Sanʿaʾ as his capital and instituted the Fatimid Ismaʿili khutba throughout his dominions. The Sulayhids ruled over Yemen as vassals of the Fatimids for almost one century. Sulayhid rule was effectively terminated in 532/1138, on the death of the queen Sayyida, the most capable member of the dynasty.

Asma bint Shihab

ʿAli b. Muhammad al-Sulayhi was married to his cousin Asma bint Shihab, a remarkable woman in her own right. Noted for her independent character, Asma took an active part in the affairs of the state and also played an important role in the education of Sayyida Hurra, who was brought up under her care at the Sulayhid court. ʿAli al-Sulayhi fell victim to a tribal vendetta and was murdered by the Najahids of Zabid in 459/1067; he was succeeded by his son Ahmad al-Mukarram (d. 477/1084), who received his investiture from the Fatimid caliph-imam al-Mustansir. The queen Asma assisted her son Ahmad, as she had assisted her husband, until her death in 467/1074. Thereafter, Ahmad's wife, Sayyida Hurra, became the effective ruler of Sulayhid Yemen.

Al-Sayyida al-Hurra

The queen [al-malika] al-Sayyida al-Hurra [the Noble Lady] al-Sulayhi, who evidently also carried the name Arwa, was born in 440/1048 (or less probably in 444/1052) in Haraz. As noted, her early education was supervised by her future mother-in-law, Asma, who as a role model must have had great influence on Sayyida's character. Ahmad al-Mukarram, who proved to be an incapable ruler, married Sayyida in 458/1066. The sources unanimously report that Sayyida was not only endowed with striking beauty, but was also noted for her courage, integrity, piety, and independent character as well as intelligence. In addition, she was a woman of high literary expertise. Almost immediately on Asma's death, Sayyida consolidated the reins of the Sulayhid state in her own hands and had her name mentioned in the khutba after that of the Fatimid caliph-imam al-Mustansir. Ahmad al-Mukarram, who had been afflicted with facial paralysis resulting from war injuries, now retired completely from public life while remaining the nominal ruler of the Sulayhid state. One of Sayyida's first acts was to transfer the seat of the Sulayhid state from Sanʿaʾ to Dhu Jibla. She built a new palace there and transformed the old palace into a great mosque where she was eventually buried.

The re-establishment of the Ismaʿili daʿwa

In the meantime, the foundation of the Sulayhid dynasty had marked the initiation of a new, open phase in the activities of the Ismaʿili daʿwa in Yemen; and the reinvigoration of the Yemenite daʿwa continued unabated in Sayyida's time under the close supervision of the Fatimid daʿwa headquarters in Cairo. The founder of the Sulayhid dynasty, ʿAli b. Muhammad al-Sulayhi, had been the head of the state [dawla] as well as the daʿwa; he was at once the malik or sultan and the chief daʿi of Yemen. Subsequently, this arrangement went through several phases, leading to an entirely independent status for the head of the daʿwa.8 In 454/1062, ʿAli sent Lamak b. Malik al-Hammadi, then chief qadi of Yemen, on a diplomatic mission to Cairo to prepare for his own visit there. For unknown reasons, however, ʿAli's visit to the Fatimid headquarters never materialized, and the qadi Lamak remained in Egypt for almost five years, staying with the Fatimid daʿi al-duʿat, al-Mu'ayyad fi'l Din al-Shirazi (d. 470/1078), at the Dar al-ʿIlm, which then also served as the administrative headquarters of the Fatimid daʿwa. Al-Muʿayyad instructed Lamak in Ismaʿili doctrines, as he had Nasir-i Khusraw, the renowned Ismaʿili daʿi and philosopher of Badakhshan, about a decade earlier. Lamak returned to Yemen with a valuable collection of Ismaʿili texts soon after ʿAli al-Sulayhi's murder in 459/1067, having now been appointed as the chief daʿi of Yemen. Lamak, designated as daʿi al-balagh, henceforth acted as the executive head of the Yemenite daʿwa, while Ahmad al-Mukarram succeeded his father merely as the head of state. The exceptionally close ties between the Sulayhids and the Fatimids are well attested to by numerous letters and epistles [sijillat] sent from the Fatimid chancery to the Sulayhids ʿAli, Ahmad, and Sayyida, mostly on the orders of al-Mustansir.9

Hurra's ascension in the Fatimid daʿwa

It is a testimony to Sayyida Hurra's capabilities that, from the time of her assumption of effective political authority, she also came to play an increasingly important role in the affairs of the Yemenite daʿwa, which culminated in her appointment as the hujja of Yemen by the Fatimid al-Mustansir shortly after the death of her husband in 477/1084. It is to be noted that in the Fatimid daʿwa hierarchy, this rank was higher than that of the daʿi al-balagh accorded to Lamak.10 In other words, Sayyida now held the highest rank in the Yemenite daʿwa. More significantly, this represented the first application of the rank of, hujja, or indeed any high rank in the Ismaʿili hierarchy, to a woman; a truly unique event in the history of Ismaʿilism.

In the Fatimid daʿwa organization, the non-Fatimid regions of the world were divided into twelve jaziras, or islands; each jazira, representing a separate and independent region for the propagation of the daʿwa, was placed under the jurisdiction of a high ranking daʿi designated as hujja. Yemen does not appear among the known Fatimid lists of these jaziras.11 However, it seems that the term hujja was also used in a more limited sense in reference to the highest Ismaʿili dignitary of some particular regions; and it was in this sense that Sayyida was designated as the hujja of Yemen, much in the same way that her contemporary Fatimid daʿi of the eastern Iranian lands, Nasir-i Khusraw, was known as the hujja of Khurasan. At any event, the hujja was the highest representative of the daʿwa in any particular region. In addition to the testimony of the daʿi Idris, the Fatimid al-Mustansir's designation of Sayyida as the hujja of Yemen is corroborated by the contemporary Yemenite Ismaʿili author al Khattab b. al-Hasan (d. 533/1138), who uses various arguments in support of this appointment and insists that even a woman could hold that rank. 12

Responsibilities

The queen Sayyida was also officially put in charge of the affairs of the Ismaʿili daʿwa in western India by the Fatimid caliph-imam al-Mustansir.13 The Sulayhids had evidently with the approval of the Fatimid daʿwa headquarters supervised the selection and dispatch of daʿis to Gujarat in western India. Sayyida now played a particularly crucial role in the Fatimids' renewed efforts in al-Mustansir's time to spread Ismaʿilism on the Indian subcontinent. As a result of these Sulayhid efforts, a new Ismaʿili community was founded in Gujarat by the daʿis sent from Yemen starting around 460/1067-68. The daʿwa in western India maintained its close ties with Yemen in the time of the queen Sayyida; and the Ismaʿili community founded there in the second half of the fifth/eleventh century evolved into the modern Tayyibi Bohra community. It should be added in passing that the extension of the Ismaʿili daʿwa in Yemen and Gujarat in al Mustansir's time may have been directly related to the development of new Fatimid commercial interests which necessitated the utilization of Yemen as a safe base along the Red Sea trade route to India.

Nizari-Mustaʿli schism

It was also in Sayyida's time that the Nizari-Mustaʿli schism of 487/1094 occurred in Ismaʿilism. This schism, revolving around al-Mustansir's succession, split the then unified Ismaʿili community into two rival factions, the Mustaʿliyya who recognized al-Mustansir's successor on the Fatimid throne, al-Mustaʿli, also as their imam; and the Nizariyya, who upheld the rights of al-Mustansir's eldest son and original heir-designate, Nizar, who had been set aside by force through the machinations of the all-powerful Fatimid vizier al-Afdal. After the failure of his brief revolt, Nizar himself was captured and murdered in Cairo in 488/1095.

Due to the close relations between Sulayhid Yemen and Fatimid Egypt, the queen Sayyida recognized al-Mustaʿli as the legitimate imam after al-Mustansir. She, thus, retained her ties with Cairo and the daʿwa headquarters there, which now served as the center of the Mustaʿlian daʿwa. As a result of Sayyida's decision, the Ismaʿili communities of Yemen and Gujarat along with the bulk of the Isma'ilis of Egypt and Syria joined the Mustaʿlian camp without any dissent. By contrast, the Ismaʿilis of the eastern lands, situated in the Saljuk dominions, who were then under the leadership of Hasan-i Sabbah (d. 518/1124), championed the cause of Nizar and refused to recognize the Fatimid caliph al-Musta'li's imamate. Hasan-i Sabbah, who had already been following an independent revolutionary policy from his mountain headquarters at Alamut in northern Persia, completely severed his relations with Cairo; he had now in fact founded the independent Nizari daʿwa, similarly to what the queen Sayyida was to do for the Mustaʿli-Tayyibi daʿwa a few decades later.

Al-Afdal

The queen Sayyida remained close to the Fatimid al-Mustaʿli (487-95/1094-1101) and his successor al-Amir (495-524/1101-30), who addressed her with several honorific titles.14 Until his death in 515/1121, the vizier and commander of the armies, al-Afdal, was however the effective ruler of Fatimid Egypt, also supervising the affairs of the Mustaʿlian daʿwa. During this period, the Fatimid state had embarked on its rapid decline, which was accentuated by encounters with the Crusaders. Egypt was in fact invaded temporarily in 511/1117 by Baldwin I, king of the Latin state of Jerusalem. In Yemen, too, the Sulayhid state had come under pressures from the Zaydis and others, while several influential Yemenite tribal chiefs had challenged without much immediate success Sayyida's authority. In particular, the qadi ʿImran, who had earlier supported the Sulayhids, attempted to rally the various Hamdani clans against her. In addition to resenting the authority of a female ruler, he also had his differences with the daʿi Lamak. As a result of these challenges, the Sulayhids eventually lost Sanʿaʾ to a new Hamdani dynasty supported by the family of the qadi ʿImran. Meanwhile, Sayyida had continued to look after the affairs of the Yemenite daʿwa with the collaboration of its executive head, Lamak; and on Lamak's death around 491/1098, his son Yahya took administrative charge of the daʿwa until his own death in 520/1126.

There are indications suggesting that during the final years of al-Afdal's vizierate, relations deteriorated between the Sulayhid queen and the Fatimid court. It was perhaps due to this fact that in 513/1119 Ibn Najib al-Dawla was dispatched from Cairo to Yemen to bring the Sulayhid state under greater control of the Fatimids. However, Ibn Najib al- Dawla and his Armenian soldiers made themselves very unpopular in Yemen, and the queen attempted to get rid of him. In 519/1125, Ibn Najib al-Dawla, whose Yemenite mission had been reconfirmed by al-Afdal's successor, al-Ma'mun, was recalled to Cairo, and was drowned on the return journey. By the final years of al-Amir's rule, the queen Sayyida had developed a deep distrust of the Fatimids and was prepared to assert her independence from the Fatimid establishment. The opportunity for this decision came with the death of al-Amir and the Hafizi-Tayyibi schism in Mustaʿlian Ismaʿilism. Meanwhile, on the death of the daʿi Yahya b. Lamak al-Hammadi in 520/1126, his assistant daʿi, al-Dhu'ayb b. Musa al-Wadiʿi al-Hamdani, became the executive head of the Yemenite daʿwa. This appointment had received the prior approval of both the queen Sayyida and the daʿi Yahya.

Collapse of the Fatimid Empire

Al-Amir, the tenth Fatimid caliph and the twentieth imam of the Musta'lian Ismaʿilis, was assassinated in Dhu'l-Qaʿda 524/October 1130. Henceforth, the Fatimid caliphate embarked on its final phase of decline and collapse, marked by numerous dynastic, religious, political, and military crises, while a new schism further weakened the Mustaʿlian daʿwa. According to the Mustaʿli-Tayyibi tradition, a son named al-Tayyib had been born to al-Amir a few months before his death. This is supported by an epistle of al-Amir sent by a certain Sharif Muhammad b. Haydara to the Sulayhid queen of Yemen, announcing the birth of Abu'l-Qasim al-Tayyib in Rabiʿ II 524AH.15 The historical reality of al-Tayyib is also attested to by Ibn Muyassar (d. 677/1278).16 and other historians. At any rate, al-Tayyib was immediately designated as al-Amir's heir. On al-Amir's death, however, power was assumed by his cousin, Abu'l-Maymun ʿAbd al-Majid, who was later in 526/1132 proclaimed caliph and imam with the title al-Hafiz al-Din Allah.

Mustaʿlian schism

The proclamation of al-Hafiz as caliph and imam caused a major schism in the Mustaʿlian community. In particular, his claim to the imamate, even though he was not a direct descendant of the previous Mustaʿlian imam, received the support of the official daʿwa organization in Cairo and the majority of the Mustaʿlian Ismaʿilis of Egypt and Syria, who became known as the Hafiziyya. The situation was quite different in Yemen. There, a bitter contest rooted in power politics ensued within the Mustaʿlian community. As a result, the Yemenite Ismaʿilis, who had always been closely connected with the daʿwa headquarters in Cairo, split into two factions. The Sulayhid queen, who had already become disillusioned with Cairo, readily championed the cause of al-Tayyib, recognizing him as al-Amir's successor to the imamate. These Ismaʿilis were initially known as the Amiriyya, but subsequently, after the establishment of the independent Tayyibi daʿwa in Yemen, they became designated as the Tayyibiyya. Sayyida now became the official leader of the Tayyibi faction in Yemen, severing her ties with Cairo, similarly to what Hasan-i Sabbah had done in Persia on al-Mustansir's death in 487/1094. Sayyida's decision was fully endorsed by the daʿi al-Dhu'ayb, the administrative head of the Yemenite daʿwa. By contrast, the Zurayʿids of ʿAdan and some of the Hamdanids of Sanʿaʾ, who had won their independence from the Sulayhids, now supported Hafizi lsmaʿilism, recognizing al-Hafiz, and later Fatimid caliphs as their imams. Hafizi lsmaʿilism, tied to the Fatimid regime, disappeared soon after the collapse of the Fatimid dynasty in 567/1171 and the Ayyubid invasion of southern Arabia in 569/1173. But the Tayyibi daʿwa, initiated by Sayyida, survived in Yemen with its headquarters remaining in Haraz. Due to the close ties between Sulayhid Yemen and Gujarat, the Tayyibi cause was also upheld in western India, which was eventually to account for the bulk of the Tayyibi Ismaʿilis, known there as Bohras.

Al-Tayyib

Nothing is known about the fate of al-Tayyib, who seems to have been murdered in his infancy on al-Hafiz's order. It is, however, the belief of the Tayyibis that al-Tayyib survived and went into concealment; and that the imamate subsequently continued secretly in his progeny, being handed down from father to son, during the current period of satr [concealment] initiated by al-Tayyib's own concealment. The news of al-Tayyib's birth was a source of rejoicing at the Sulayhid court. For this event, we also have the eyewitness report of al-Khattab, who was then assistant to the daʿi al-Dhu'ayb.17 From that time until her death, the aged Sulayhid queen made every effort to consolidate the Yemenite daʿwa on behalf of al-Tayyib; and al-Dhu'ayb and other leaders of the daʿwa in Sulayhid Yemen, henceforth called al-daʿwa al-Tayyibiyya, collaborated closely with Sayyida. It was soon after 526/1132 that Sayyida declared al-Dhu'ayb as al-daʿi al-mutlaq, or daʿi with absolute authority. Having earlier broken her relations with Fatimid Egypt, by this measure she also made the Tayyibi daʿwa independent of the Sulayhid state, a wise measure that was to ensure the survival of Tayyibi Ismaʿilism after the downfall of the Sulayhid state. The daʿi mutlaq was now in fact empowered to conduct the daʿwa activities on behalf of the hidden Tayyibi imam. This marked the foundation of the independent Tayyibi daʿwa in Yemen under the leadership of a daʿi mutlaq, a title retained by al-Dhu'ayb's successors.18 The daʿi al-Dhu'ayb thus became the first of the absolute daʿis, who have followed one another during the current period of satr in the history of Tayyibi Ismaʿilism.

Tayyibi daʿwa

As noted, al-Dhu'ayb was initially assisted by al-Khattab b. al-Hasan, who belonged to a family of the chiefs of al-Hajur, another Hamdani clan. An important Ismaʿili author and Yemenite poet, al-Khattab himself was the Hajuri sultan who fought as a brave warrior on behalf of the Sulayhid queen. His loyalty to Sayyida Hurra and his military services to the Ismaʿili cause contributed significantly to the success of the early Tayyibi daʿwa in difficult

times. Al-Khattab was killed in 533/1138, a year after the queen had died. On al- Khattab's death, al-Dhu'ayb designated Ibrahim b. alHusayn al-Hamidi, belonging to the Hamidi clan of the Banu Hamdan, as his new assistant; and on al-Dhu'ayb's death in 546/1151, Ibrahim (d. 557/1162) succeeded to the headship of the Tayyibi daʿwa as the second daʿi mutlaq. Al Dhu'ayb, al-Khattab, and Ibrahim were in fact the earliest leaders of the Tayyibi daʿwa who, under the supreme guidance and patronage of Sayyida, consolidated this branch of lsmaʿilism in Yemen. The Tayyibi daʿwa had now become completely independent of both the Fatimid regime and the Sulayhid state, and this explains why it survived the fall of both dynasties and managed in subsequent centuries, without any political support, to spread successfully in Yemen and western India. That the minoritarian Mustaʿli-Tayyibi community of the Ismaʿilis exists at all today is indeed mainly due to the foresight and leadership of Sayyida Hurra, much in the same way that the survival of the majoritarian Isma'ili community of the Nizaris may be attributed in no small measure to the success of Hasan-i Sabbah in founding the independent Nizari daʿwa, while in both instances the imams themselves had remained inaccessible to their followers.

End of the Sulayhid dynasty

The Malika Sayyida Hurra bint Ahmad al-Sulayhi died in 532/1138, after a long and eventful rule. Her death marked the effective end of the Sulayhid dynasty, which held on to some scattered fortresses in Yemen for a few decades longer. A most capable ruler, Sayyida occupies a unique place in the annals of Ismaʿilism, not only because she was the sole woman to occupy the highest ranks of the Ismaʿili daʿwa hierarchy and to lead the Yemenite daʿwa in turbulent times, but more significantly because she in effect was largely responsible for the founding of the independent Mustaʿli Tayyibi daʿwa, which still has followers in Yemen, India, Pakistan, and elsewhere. It should also be noted here that the Tayyibi Ismaʿilis have been responsible for preserving a large portion of the Ismaʿili texts produced during the Fatimid period, and the preservation of this Ismaʿili literature too may be attributed largely to Sayyida's foresight. The queen Sayyida's devotion to Ismaʿilism and the cause of al-Tayyib found its final expression in her will in which she bequeathed her renowned collection of jewelry to Imam al-Tayyib.19

This remarkable Ismaʿili Sulayhid woman of the medieval Islamic world was buried in the mosque of Dhu Jibla that she had erected herself. And throughout the centuries, Sayyida's grave has served as a place of pilgrimage for Muslims of diverse communities; the pilgrims not always being aware of her Ismaʿili Shiʿi connection. Various attempts were made in medieval times by Zaydis and other enemies of the Ismaʿilis in Yemen to destroy the mosque of Dhu Jibla; but Sayyida Hurra's tomb chamber, inscribed with Qurʾanic verses, remained intact until it, too, was damaged in September 1993 by members of a local group who considered the established practice of visiting it to be heretical.20

- See Idris ʿImad al-Din b. al-Hasan, ʿUyun al-akhbar wa funun athar, ed. M. Ghalib (Beirut: Dar al-Andalus, 1973-78), vol. 5, pp. 137-38, reprinted in S.M. Stern, Studies in Early Ismaʿilism (Jerusalem-Leiden: The Magnes Press, 1983), pp. 102-103.

- Taqi al-Din Ahmad b. ʿAli al-Maqrizi, Kitab al-mawa iz wa' l-i'tibar bi-dhikr al-khitat wa'l athar (Bulaq, 1270/1853-54), vol. 1, pp. 390-91. and vol. 2, pp. 341-42. See also H. Halm, "The Isma'ili Oath of Allegiance ('ahd) and the 'Sessions of Wisdom' (majalis al-hikma) in Fatimid Times," in Mediaeval lsmaʿili History and Thought, ed. F. Daftary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), especially pp. 98-112, and H. Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning (London: I.B. Tauris, 1997), pp. 41-56.

- See Ibn al-Tuwayr, Nuzhat al-muqlatayn fi akhbar al-dawlatayn, ed. A. Fu'ad Sayyid (Stuttgart: F. Steiner, 1992), pp. 110-112, and S.M. Stern "Cairo as the Centre of the Ismaʿili Movement," in Colloque international sur l'histoire du Caire (Cairo: Ministry of Culture, 1972, p. 441, reprinted in Stern, Studies, pp. 242- 43.

- 'Umara b. ʿAli al-Hakami, Ta'rikh al-Yaman, ed. and trans. Henry C. Kay, in his Yaman, its Early Mediaeval History (London: E. Arnold, 1892), text pp. 1-102, translation pp. 1-137; more recently, this history has been edited by Hasan S. Mahmud (Cairo: Maktabat Misr, 1957).

- See Idris 'Imad al-Din, ʿUyun al-akhbar, vol. 7, Arabic manuscript 230, The Institute of Ismaili Studies Library, London, containing the history of the Sulayhids on fols. 1-222, with fols. 117v-222v devoted to Sayyida Hurra. See A. Gacek, Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts in the Library of The Institute of Ismaili Studies (London: Islamic Publications, 1984-85), vol. 1, pp.136- 40.

- In this article I have drawn on the following works by H.F. al-Hamdani: "The Doctrines and History of the Ismaʿili Daʿwat in Yemen," (Ph.D. thesis, University of London, 1931), especially pp. 27-47; "The Life and Times of Queen Saiyidah Arwa the Sulaihid of the Yemen," Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society 18 (1931): 505-17, and al-Sulayhiyyun wa'1haraka al-Fatimiyya fi'l--Yaman (Cairo: Maktabat Misr, 1955), especially pp. 141-211, which is still the best modern study on the subject. Some recent publications on Sayidda Hurra, including L. al-Imad's "Women and Religion in the Fatimid Caliphate: The Case of al-Sayyida al-Hurra, Queen of Yemen," in Intellectual Studies on Islam: Essays written in Honor of Martin B. Dickson, ed. M.M. Mazzaoui and V.B. Moreen (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990), pp. 137-44, and Fatima Mernissi's The Forgotten Queens of Islam, trans. M.J. Lakeland (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993), pp. 139-58, provide new perspectives without adding significant details to al-Hamdani's studies. See also F. Krenkow, s.v. "Sulaihi," EI(I), ed. M.Th. Houtsma et al. (Leiden-London: E.J. Brill, 1913-38), Vol. 4, pp. 515-17; M. Ghalib, Aʿlam al Ismaʿiliyya (Beirut: Dar al-Yaqza, 1964), pp. 143-53; Khayr al-Din al-Zarkali, al-A'lam, 3rd ed. (Beirut: Khayr al-Din al-Zarikli, 1969), vol. I, p. 279, and ʿUmar R. Kahhala, Aʿlam al-nisa', 3rd ed. (Beirut: Mu'asisat al-Risala, 1999), vol. 1, pp. 253-54.

- See Idris, ʿUyun al-akhbar, vol. 5, pp.31-44; Ibn Malik al-Yamani, Kashf asrar al-Batiniyya wa-akhbar al-Qaramita, ed. M.Z. al-Kawthari (Cairo: Matabʿat al-Anwar, 1939), pp. 39-42, written for a Yemenite Sunni jurist who lived at the time of the founder of the Sulayhid dynasty; he later became an Ismaʿili but then abjured and produced this anti-Ismaʿili treatise which is also reproduced in Akhbar al-Qaramita, ed. S. Zakkar, 2nd ed. (Damascus: Dar Nissan, 1982), pp. 243-48. Ibn Malik's work evidently served as the primary source on the early Ismaʿili daʿwa in Yemen for all subsequent Sunni historians of Yemen, including Baha al-Din al-Janadi (d. 732/1332), who reproduces Ibn Malik's list of the Yemenite daʿis in his Akhbar al-Qaramita bi'l Yaman, ed. and trans. Kay, in his Yaman, text pp. 150-52, translation pp. 208-12. See also al Hamdani, al-Sulayhiyyun, pp. 49 - 61.

- A. Hamdani, "The daʿi Hatim Ibn Ibrahim al-Hamidi [d. 596 H/1199AD] and his Book Tuhfat al-Qulub," Oriens 23-24 (1970-71): especially 270-79.

- See Abu Tamim Ma'add al-Mustansir bi'llah, al-Sijillat al-Mustansiriyya, ed. 'Abd al Mun'im Majid (Cairo: Dar al-Fikr al-'Arabi, 1954), and H.F. al-Hamdani, "The Letters of al Mustansir bi'llah," Bulletin of the School of Oriental (and African) Studies 7 (1934): 307-24, describing the contents of the letters.

- F Daftary, The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 227ff.

- See al-Qadi al-Nuʿman b. Mubammad, Ta'wil al-daʿa'im, ed. M. H. al-A'zami (Cairo: Dar al-Ma'irif bi-Misr, 1967-72), vol. 2, p. 74, and vol. 3, pp. 48-49; Abu Ya'qub al-Sijistani, Ithbat al-nubuwwat, ed. 'Arif Tamir (Beirut: al-Matba'a al-Kathulikiyya, 1966), p. 172; Ibn Hawqal, Kitab surat al-ard ed. J. H. Kramers, 2nd ed. (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1938-39), p. 310, and Daftary, The Ismailis, pp. 228-2.9.

- Al-Khattab b. al-Hasan, Ghayat al-mawalid, Arabic manuscript 249. The Institute of Ismaʿili Studies Library, London, fols. 4r-8r; see Gacek, Catalogue, vol. 1, p. 21. See also I.K. Poonawala, al-Sultan al-Khattab (Cairo: Dar al-Ma'arif bi-Misr, 1967), pp.78-80, and S.M. Stern, "The Succession to the Fatimid Imam al-Amir, the Claims of the Later Fatimids to the Imamate, and the Rise of Tayyibi Ismaʿilism," Oriens, 4 (1951): 221, 227-28, reprinted in S.M. Stern, History and Culture in the Medieval Muslim World (London: Variorum Reprints, 1984), article XI.

- Al-Mustansir, al-Sijillat, pp. 167-69, 203-06, and al-Hamdani, "Letters," pp. 321-24.

- See al-Maqrizi, Ittiʿaz al-hunafa', ed. J. al-Shayyal and M.H.M. Ahmad (Cairo, 1967-73), vol. 3, p. 103.

- This sijill is preserved in the seventh volume of the ʿUyun al-akhbar of the daʿi Idris and in other Tayyibi sources; it is also quoted in 'Umara, Ta'rikh, text pp. l00-102, translation pp. 135- 36. See also Stern, "Succession," p. 194ff, and al-Hamdani, al-Sulayhiyyun, pp. 183-84, 321-22.

- Ibn Muyassar, Akhbar Misr, ed. A. Fu'ad Sayyid (Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale,1981), pp. 109-110.

- The relevant passage from al-Khattab's Ghayat al-mawalid is also contained in W. Ivanow, Ismaʿili Tradition Concerning the Rise of the Fatimids (London. H. Milford for the Islamic Research Association, 1942.), pp. 37-38; English translation in Stern, "Succession," pp. 223-24.

- The earliest history of the Tayyibi daʿwa in Yemen is related by the daʿi Hatim b. Ibrahim in his unpublished Tuhfat al-qulub. The daʿi Idris has biographical accounts of al-Dhu'ayb and his successors in his unpublished 'Uyun al-akhbar, vol. 7, and Nudhat al-afkar. See also Daftary, The Ismailis, p. 285ff.

- Sayyida's testament, containing a detailed description of her collection of jewels, has been preserved by Idris in his ʿUyun al-akhbar, vol. 7, reproduced in al-Hamdani, al-Sulayhiyyun,

- I owe this information to Tim Mackintosh-Smith, a long-time resident of Yemen.

Author

Dr Farhad Daftary

Co-Director and Head of the Department of Academic Research and Publications

An authority in Shi'i studies, with special reference to its Ismaili tradition, Dr. Daftary has published and lectured widely in these fields of Islamic studies. In 2011 a Festschrift entitled Fortresses of the Intellect was produced to honour Dr. Daftary by a number of his colleagues and peers.

The use of materials published on the Institute of Ismaʿili Studies website indicates an acceptance of the Institute of Ismaʿili Studies’ Conditions of Use. Each copy of the article must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed by each transmission. For all published work, it is best to assume you should ask both the original authors and the publishers for permission to (re)use information and always credit the authors and source of the information.

© 1980 His Highness Prince Aga Khan Shia Imami Ismaʿilia Association for Kenya

© 1981 Literature & Publication Department of His Highness Prince Aga Khan Shia Imami Ismaʿilia Association for the United Kingdom

© 2003 The Institute of Ismaʿili Studies