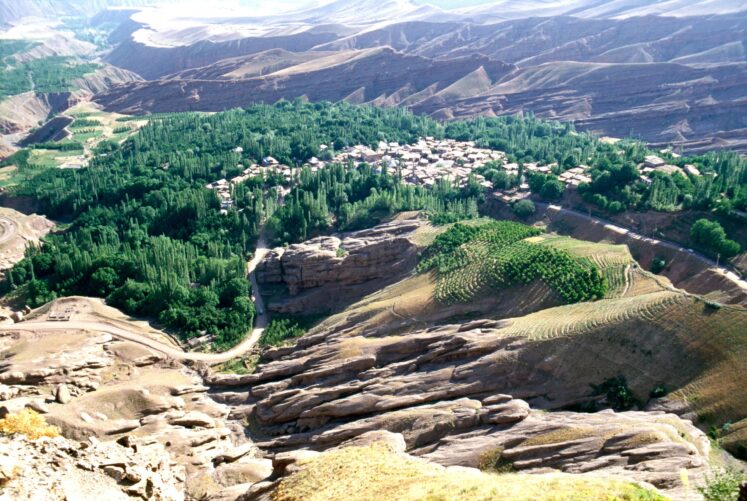

Stretching as it does from Garmarud in the east to the Shirkuh gorge in the west, the Valley of Alamut is bounded by mountain walls to the north, south, and east.

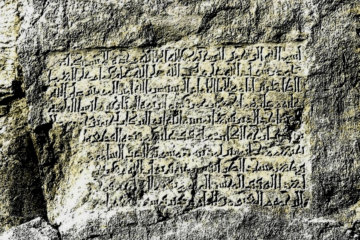

Its isolation was the main reason for the Persian Ismaili daʿi Hasan-i Sabbah to establish his power base here in the late 11th century, and for him and the other lords (khudawands) of Alamut being able to defend the IsmailisAdherents of a branch of Shi’i Islam that considers Ismail, the eldest son of the Shi’i Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 765), as his successor. against sustained attack until the onslaught of the Mongols in the 13th.

There are 60 or so Ismaili castles, forts, and watchtowers in the Alamut Valley, including the major fortresses of Alamut, Bidilan, Maymundiz, Samiran, and Garmarud.

Alamut is about 120 km from Tehran and 40 km from Qazvin. The mule-track access of up until the late 1950s was replaced by a dirt road which, in turn, was replaced by a new main road running from Tehran to Qazvin which links to a tarmac road, constructed at the time of the last Shah of Iran, into Alamut.

All the road signs point towards Alamut, including one marking the official entry into the valley. Clearly, as Peter Willey notes, ‘After 900 years of isolation, Alamut is…[a] popular tourist attraction’, enabling visitors from Tehran to drive there, ‘a common Friday holiday trip’, ‘have a picnic lunch, and return the same day’.

The scale of the natural landscape is a wondrous sight to behold.

The steep slopes are a marvel from the tarmac road, itself ‘a triumph of engineering, rising and falling in a series of startling bends and curves, often at acute angles, and afford[ing] a magnificent panorama of the Alborz scenery.’

East of the Alamut Valley is the 4,500 m mountain-knot of ʿAlam-kuh/Takht-i Sulayman, with a nearby peak marking the source of the Alamut-rud (Alamut river), which descends steeply — about 1,500 m — to the village of Garmarud and at the foot of the castle of Nivizarshah.

With mountain ranges up to 3,050 m to the north and the south, the Alamut-rud continues westward 40 km through the valley, which is 15 km at its widest, ultimately joining the Taliqan river in the gorge overlooked by the castles of Shirkuh and Bidilan in the west.

The 350 m deep Shirkuh gorge is impassable for half the year, filling with rainy winter floodwaters as much as with spring meltwaters. The valley of the Alamut-rud could thus be defended along its entire length — on the western gorge, with the fortresses of Shirkuh and Bidilan, and on the eastern mountain passes with the castle of Nivizarshah.

In the middle lies the seemingly banal but in fact vital and often-overlooked agricultural basis of Ismaili power — land, flat and fertile, tillable for wheat and cattle feed as much as irrigable for rice — sustaining the community of that time and space in an otherwise arid and inhospitable landscape.

And at the heart of the Valley of Alamut, protected by the surrounding castles and mountain walls even as it surveyed and protected that land, lies that iconic site of the Ismailis in history, the stuff of myth and legend, the Castle of Alamut.

But that’s for another story.

References

Peter Willey. Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. London & New York: I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies. 2005, pp. 103–104.

Source, CRediTs, and Acknowledgements

IRN0001S – Alamut Valley. Ismaili Heritage Database. Ismaili Heritage Project, The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2023.

Shayesteh Ghofrani: Investigation, Writing – Original Draft; Sorbon Mavlonazarov: Validation, Visualisation, Data Curation; Maryam Rezaee: Validation, Visualisation, Data Curation; Lisa Morgan: Writing – Review and Editing; Fayaz S Alibhai: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualisation, Supervision, Project Administration; Shiraz Allibhai: Conceptualisation; Nazir Mulji: Conceptualisation; Zayn Kassam: Conceptualisation; Abdul Javery: Software, Data Curation; Shoaib Momin: Software, Data Curation; Javed Merchant: Software, Data Curation; Nuresh Momin: Software, Data Curation.

About

The Ismaili Heritage Project is a tripartite collaboration between IIS (London), the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (Geneva), and the Department of Jamati Institutions (Lisbon). The project aims to document, protect, conserve, and celebrate the built and associated tangible heritage of the global Shia Ismaili Muslims.