History textbooks frequently lack female perspectives and overlook the personal experiences of women as various communities evolve. The Graduate Programme in Islamic Studies and Humanities (GPISH) inspired me to see and read Ismaili history through the lens of women in my family, in order to uncover what my grandmother and great-grandmother witnessed, felt, and experienced growing up in rural Sindh, and how their faith and social surroundings evolved with time. The Oral History Project of the Ismaili Special Collections Unit (ISCU) allowed me to embark upon this mission in March 2023, when I had an opportunity to interview my grandmother Zebunissa and to document her life story for the project.

➤ Zebunnisa. Image credit: Shafaat Saleem, 2023.

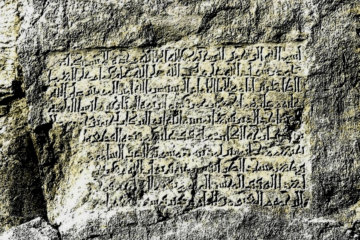

Zebunissa, who is now 71, migrated from the old town to new Ismaili settlements in Hyderabad, Pakistan, in the late 20th century. She grew up with six sisters and three brothers in a pluralistic and peaceful area called Hirabad in Hyderabad, Pakistan. Unlike Zebunissa’s current residential area, the neighbourhood of Hirabad was culturally and religiously diverse. Her family lived in shared apartments and had good relations with non-Ismaili Muslims and Hindus in the area. As she narrates, ‘non-Ismailis were like brothers and sisters for us, and they used to help us in difficult times. Hindus [also] lived there, and we never had any issues. At times, we used to eat together.’

Zebunissa, in recalling the stories told by her mother, mentioned that things started to change after the partition of the Indian Subcontinent in 1947. The Hindu residents of Hirabad migrated to what became India, and their homes and lands were taken over by Muslims who stayed behind in the district that became part of Pakistan. In this way, Zebunissa’s elders became landlords after Partition, having acquired lands from the departing Hindus. With minimal formal education, Zebunissa’s family remained focused on economic stability and a sustainable income. She, and most of her siblings, was married at a young age.

➤ Former Ismaili settlements in Hirabad (sometimes spelt Heerabad and translated as “Diamond Town”). It is one of the oldest parts of the city of Hyderabad in Sindh, Pakistan. Image credit: Shafaat Saleem, 2023.

After the death of her first husband, Zebunissa was then married to her cousin. At that time, it was not a social norm for widows to remarry. However, her family decided to remarry her following the guidance of the Ismaili Imam, the religious and spiritual leader of the Ismaili Muslim community.

In her words: ‘During those days, Hazar Imam visited Hyderabad. He gave a farman stating that all young widows should remarry if they want. He said there was no harm in remarrying for better futures and lives. My father followed this farman and wedded me off to my cousin. During my second nikah, when we went to the Mukhi Saheb for blessings in the Jamatkhana, everyone stood up to give us blessings and said, “this is the first couple in Hyderabad who have followed Hazar Imam’s farman.” After that, many other widowed people remarried. But I was the first one.’ Zebunissa’s second marriage, contracted following the guidance of the Imam, became a gateway for many widows in the community to better their lives. More importantly, this shows how the Imam-of-the-Time enabled communal and social prosperity and laid out a path for future generations of women in Ismaili communities.

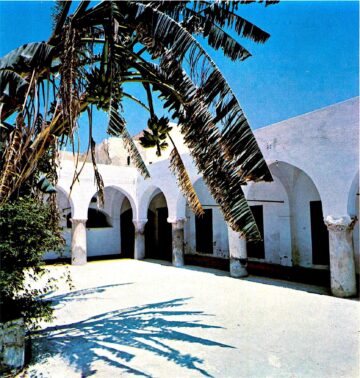

➤ A former Ismaili residence in Hirabad. Image credit: Shafaat Saleem, 2023.

Zebunissa’s story also reveals how community development initiatives taken by Ismaili institutions transformed the domestic lives and experiences of women. Years later, Zebunissa and her family moved to the newly constructed and gated micro-neighbourhood, ‘the Mubarak Housing Society’, commonly known as Mubarak Colony. The housing society was built on a plot purchased by Ismaili entrepreneurs and paved the way for many upper-middle-class Ismailis towards a safe and progressive lifestyle. With the support of her father, Zebunissa was able to have a bungalow constructed in the colony.

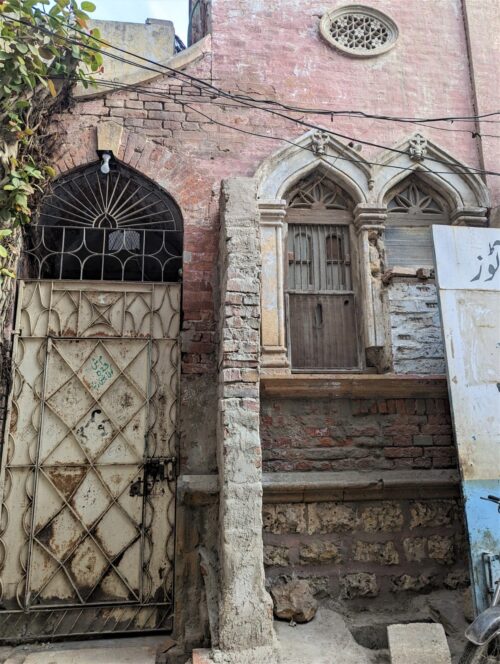

When I asked her why she moved to this new colony, she replied: ‘The area had become dangerous for us as there was a rise in drug addiction, and it was unsafe for us and the young girls to step outside and go to the Jamatkhana or anywhere else. There were around 80–100 Ismaili families and approximately 100 people were from my family in Hirabad. However, due to urbanisation, there were a lot of new businesses, shops, and an influx of new people. When women used to go to the Jamatkhana wearing nice dresses and gold jewellery, they started feeling insecure as there had been attempts to rob a few people on the streets. So, we realised it was better to move to this new colony which seemed secure, especially for my girls, and to separate from the chaotic city.’

➤ A shop run by Ismailis in Hirabad Market. This shop is named after the late Prince Karim Aga Khan IV and the title in Sindhi reads “Shah Karim Grocery and Spice Shop”. The shop also sold henna and medicines to treat domestic animals. Image credit: Shafaat Saleem, 2023.

We often do not realise this in our everyday life, but the presence of gated communities, like the Mubarak Colony, empowered Ismaili women and young girls to live peacefully. Zebunissa and her family adjusted smoothly and instantly. The Aga Khan School and Hospital, built by the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) within the colony, provided the necessary educational and health infrastructure. The rapid urbanisation and construction of schools and colleges also shifted the community’s focus towards education. Mubarak Colony built a close community system and Zebunissa and her family took leadership positions in the religious and social spaces. In general, Zebunissa portrayed their move into the new colony as a significant event which transformed her everyday life and communal activities.

➤ Main entrance of the Hirabad Jamatkhana. Image credit: Shafaat Saleem, 2023.

Zebunissa’s life story gives a snapshot of key developments within the Ismaili community of Hyderabad and shows how several changes within the Ismaili community, such as encouraging widowed women to remarry, the construction of gated communities, and the building of schools and hospitals nearby, led to the ‘modernisation’ of women and their experiences. These changes shifted the socio-cultural dynamics of the community allowing women to be safer, healthier and educated. Women’s engagement in various religious activities increased and their social systems became stronger and firmer.

➤ Shops in front of Hirabad jamatkhana. Image credit: Shafaat Saleem, 2023.

My overall experience of collecting my grandmother’s life story for the Oral History Project, along with the history of the Ismaili community in rural Sindh being explored from a woman’s perspective, has allowed me to acquire a unique take on Ismaili history. I discovered details like the ways in which Ismaili women perceived their relationships with their non-Ismaili neighbours, their family dynamics and priorities, and how changes in the wider community transformed and ‘modernised’ their lives. Such details are usually absent in conventional and mainstream historical sources. However, these details are important, especially because these historical events and transformations eventually shaped my own upbringing and made me who I am today. Thus, diving into the life story of my grandmother Zebunissa not only uncovered rare historical anecdotes but also made me learn about my own background and communal belongings.

➤ Zebunissa with Shafaat Saleem, her granddaughter and interviewer for the IIS Oral History Project. Image credit: Shafaat Saleem, 2023.

I am grateful for the opportunity provided by the Oral History Project and would urge the youth in our Jamat to engage with their elders, female and male, through this project. You would be restrengthening your own sense of belonging to your communities through developing your family history as well as making a unique and long-lasting contribution to the historical record of your own and that of the Ismaili communities at large as envisioned by the uniquely designed Oral History Project.

Shafaat Saleem

Shafaat Saleem (GPISH, 2021) gained her MSc in Social Policy from the London School of Economics. She is currently pursuing a PhD at Nova University in Lisbon in anthropology, focused on the relationship between Islam and development in the context of the Aga Khan Development Network and the Ismaili Imamat in Portugal.