The Ismaili Special Collections Unit in collaboration with Department of Communications and Development has released the third episode titled, An Early Source of Shi’i Piety: al-Ṣaḥīfa al-Sajjādiyya, as part of its video series, Islamic Heritage: Past and Present in celebration of Women’s History Month. It features Dr Gurdofarid Miskinzoda, Head of Shi’i Studies at the IIS.

Released in celebration of Women’s History Month, this short video features a scholar speaking about an early source of Shi‘i piety and history, highlighting its historical significance and contemporary relevance which is the aim of the video series. Dr Miskinzoda takes us on a journey of exploring a compendium of prayers, al-Sahifa al-Sajadiyya, with a focus on its context, transmission and significance, as well as the aesthetics and material aspects from the manuscript tradition of this historical work.

Ismaili Special Collections: Islamic Heritage Past and Present - An Early Source of Shi'i Piety: al-Ṣaḥīfa al-Sajjādiyya

This third episode forms part of a new series from the Ismaili Special Collections Unit and the Department of Communications and Development. The series showcases items of historical importance held at The Institute of Ismaili Studies, and highlight their contemporary relevance today.

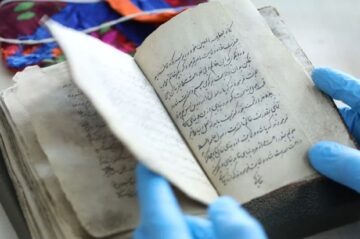

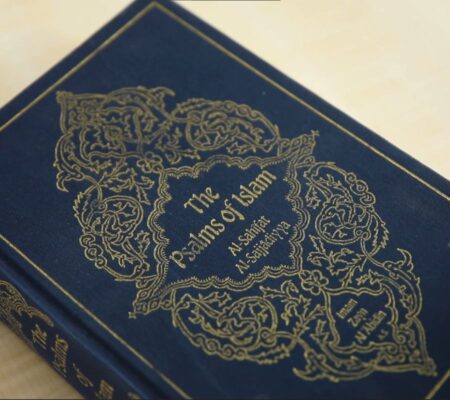

This is a manuscript of a work that relates to the early history of Shi‘i Islam. The title of the work is al-Ṣaḥīfa al-Sajjādiyya or al-Ṣaḥīfa al-Kāmila al-Sajjādiyya which can roughly be translated to English as “The Psalms…” or “The Complete Psalms of al-Sajjād“. The title of the manuscript is related to, one could even say is derived from the honorific title of one of the earliest Shi‘i imams ‘Alī b. al-Ḥusayn b. ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib who was mainly known by his honorific title, Zayn al-‘Ābidīn (the Ornament of the Worshippers) or al-Sajjād (the one who constantly prostrates in prayer and worship).

The importance of this work is based on the fact that it actually is one of the earliest sources and representatives of the Muslim historical and literary tradition, and, as many works that belong to that period, there are many issues with the history of the text but also the authorship and the history of its transmission. Therefore, many versions of this or many editions of this work contain a very long history of its transmission. This particular manuscript contains a very long history of the transmission of the text that takes us back to Muḥammad from his father which in other words means that this particular edition or this particular version of the text has been transmitted to Zayn al-‘Ābidīn through his son Muḥammad al-Bāqir and his grandson, Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq. This is essentially a du‘ā manual, a prayer manual, and, that is why it is sometimes also titled in many editions and manuscripts as al-Ṣaḥīfa al-Sajjādiyya al-Kāmila: ad‘īya wa munājāt al-Imām ‘Alī b. al-Ḥusayn Zayn al-‘Ābidīn (The Complete Psalms of the Household of the Prophet or The Complete Psalms of al-Sajjād; prayers and supplications of Imam ‘Ali b. al-Ḥusayn Zayn al-‘Ābidīn). As mentioned, it is a du‘ā manual. In fact, it is claimed to be one of the oldest du‘ā manuals and that’s why it is also known as The Complete Psalms of the Household of the Prophet.

In the complexity of studying this work is also related to the fact that there are several versions and redactions of this work but there are also more than twenty commentaries on this particular work. The most common version of the work consists of fifty-four supplications, some editions contain further fifteen munājāt (supplications). It is also translated to several languages. In particular, it has been translated to Persian as early as the Safavid Period and there is an English translation by the famous William Chittick that has been produced in the 1980s. This particular manuscript is beautifully presented, expensively decorated and it is also important because it contains a parallel Persian text in addition to the original Arabic. This makes it very useful for scholars but also for believers who speak either of the languages. They can consult either the Persian text or the Arabic or both so it becomes very useful. As I mentioned, the manuscript is beautifully and lavishly done which talks about the esteem this book was held even in the Qajar Period. It is also produced on thin gloss paper which was quite expensive at the time. It is written in a fine naskhī script and it is beautifully decorated especially the opening page is lavishly decorated. The outside of the text box is decorated in floral patterns in red, blue, green and gold and the textbox are also gilded and illuminated in the same colours. Each section begins with a text in a red gilded box which makes it very easy to distinguish where one chapter or one section begins and where the other one is ending. The colophon tells us that it has been produced in Dhū al-Ḥijja 1279 AH which coincides with May 1863 of the common era which puts it in the Qajar Period. The colophon also tells us the scribe was named ‘Alī Muḥammad b. Muḥammad al-Bāqir and it was commissioned or it was produced for a person named Āqā Mīrzā Maḥmūd. This particular text is important for at least three reasons. First, obviously this manuscript itself is a work of art. It is an example of fine Islamic bookbinding and manuscript production in particular during the Qajar Period. It also tells us about the history of transmission of this text during the Qajar Period, but it also gives us as I mentioned an indication of how important this particular work was.

In fact, it is considered one of the most popular and important texts in the Shi‘i tradition only after the Qur’an and Nahj al-BalāghaLit. ‘the way of eloquence’. A well-known collection of letters, sermons and sayings attributed to Imam ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib (d. 661 CE), compiled in its present form by al-Sharīf…, which are the collections of the sermons of the ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, the first Imam of the Shi‘a. This work is also important for a second reason because obviously being ascribed to the Shi‘i imam the content of it becomes very important. Zayn al-‘Ābidīn was the third or fourth imam of the Shi‘a depending which group you talk about. He was born about 660 in Medina. He survived the massacre of Karbala’ in 680 as a result of which his father al-Ḥusayn b. ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, which makes him the son of the first Shi‘a Imam and Fāṭima, the daughter of the Prophet, was brutally murdered. After the event of Karbala’, Zayn al-‘Ābidīn himself stayed away from direct confrontation with the authorities and chose to lead a pious life devoting himself to mainly worship, prayer and studying and that is why we have the title as al-Sajjād (the one who constantly prostrates in prayer and worship). But with the Imamat of Zayn al-‘Ābidīn, there also we see a change in the attitude of the imams and the community towards the scope and nature of the authority of the successor of the Prophet Muḥammad. First of all, the Ḥusaynid line becomes an important element in the lineage of the imams. Secondly, the nature of the authority or the station of the imamIn general usage, a leader of prayers or religious leader. The Shi’i restrict the term to their spiritual leaders descended from ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and the Prophet’s daughter, Fatima., the religious station of the imam was no longer seen to be dependant on or related to his political authority or his political office and power. We also see the beginning of the practise of taqiyyaPrecautionary dissimulation of one’s religious beliefs, especially in time of persecution or danger, a practice especially adopted by the Shi’i Muslims. (dissimulation and concealment) which eventually leads to a shift in the doctrine of imāmā the eventual articulation of which is ascribed to no other than the son of Zayn al-‘Ābidīn, Muḥammad al-Bāqir and his grandson, Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq. Thirdly, the importance of this work is obviously connected to the very content of this book.

As I mentioned, it contains prayers, supplications that are believed to be taught by Zayn al-‘Ābidīn. That in itself makes them very important for the daily practise and worship of the Shi‘a. In addition to that the content of this book is one of the finest examples of early Arabic literature in the Muslim tradition. It is an example of a very fine Arabic prose, let’s say and that makes it central. It continues to be important for the daily practice of the Shi‘a in terms of their practise of du‘ā, dhikrLit. ‘the act of reminding’; ‘remembrance’. The Qur’an exhorts individuals to remember God: ‘Oh ye who believe! Remember (udhkurū) God with much remembrance (dhikran kathīran)’ (Q. 33:41). Dhikr designates a… (remembrance) and munājāt (supplication) which are all considered different forms of worship. We are therefore very proud to house this particular manuscript in our special collections and we ensure that scholars from around the world have access to it and we also make sure that we preserve it for the future generations.