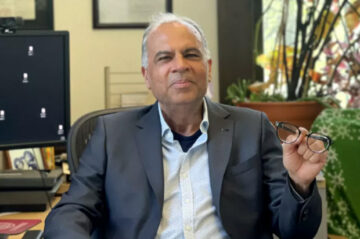

Alluding to the predicaments generated by recent world events, Azim Nanji began his talk by intimating that inherited organising principles such as the model of the nation-state and western liberal democracy, cannot be assumed to be absolute certainties. ‘We need to see things in much broader terms,’ said Nanji. ‘I think part of the difficulty is the way we rethink all of the categories that we have identified as being stable and coherent in our world. And I’m suggesting that many of these boundaries are shifting and they are shifting in dramatic ways.’ Planting what he called ‘seeds of avoidance’ and anticipating change would help educators and students to come to terms with the this time of transition and global change.

Professor Nanji stated that creating an environment where one can respect and learn about difference is an important lesson for future generations. ‘By pluralism, I don’t simply mean the existence of difference and the acknowledgement of difference. It’s the ability to negotiate difference while being respectful of it, and that negotiation is not something faith traditions have been very good at in the past.’ Speaking about religious traditions, he argued that when people’s beliefs become a vehicle for social and political agendas, you may witness the abuse of religion. ‘When faith and society are reduced to simplistic dogma, then people fail to understand how complex religious phenomena is, how it may be abused instead of being a source of constructive engagement with society.’

Citing the case of medieval Cordoba as an example in world history where pluralism emerged as a positive force, he said ‘because it was nurtured by several traditions — it was nurtured by its Mediterranean roots, it was nurtured by its Hispanic roots, but it came to be further nurtured by additional traditions that came from the Muslim world, and from the Jewish world — so what you had was a context in which three major religious traditions came together to build on a Graeco-Roman foundation and to allow for a time, a moment to appear in history where Jews, Christians and Muslims talked to each other in the same language, created a shared vocabulary and built some of the most exquisite spaces that the world has known.’

Nanji encouraged coherence and integrity in the teaching and learning of other cultures: ‘We need to work through and across frontiers.’ Speaking about international curricula, he stressed the importance of building partnerships and ensuring that local institutions take ownership, so that one is not seen as an imposing influence which dominates the educational process. Amongst the challenges in the development of contemporary curricula, Nanji emphasised the relevance of nurturing students who can embrace and manage complexity. He also underlined the importance of producing curricula that teach moral reasoning and compassion in order that ethical engagement with the world, concern for the environment and human rights are built into the moral fibre of human beings.

The annual lecture is named after Alec Peterson, one of the International Baccalaureate’s founding members and former Director of the Oxford Education Department, and coincides with the May meeting of the Council of Foundation, the IBO’s governing body.

It is anticipated that a collective volume of the Peterson Lectures given to date will soon be published by the IBO.