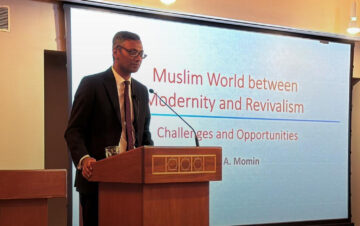

The Institute’s Director, Professor Azim Nanji spoke on “Rethinking the Muslim World in a Global Perspective” to nearly 400 attendees of Stanford’s Knight Fellowships’ 6th Reunion and Conference, held at Stanford University this past July. One of the key messages of this presentation focused on understanding the diversity among Muslim communities around the world and the specific context of their contemporary challenges.

The annual gathering of Knight Fellows brought together representatives, including 175 former fellows, from 18 countries around the world to participate in 2 days of sessions about the current state of journalism and its future, including an understanding of present day Muslims.

Beginning with a story, which is from several ancient traditions and also preserved in Muslim literature, Professor Nanji offered an insight into the challenge of conveying notions of Muslim pluralism and diversity, indicating that it is particularly relevant to the media’s understanding of the Muslim world:

A young woman walks in front of three wise men sitting on a bench. She’s clearly looking for something on that street. She spends a lot of time looking, and the three men become very interested. When she stops, they go over to her and ask ‘can we help you?’ She replies, ‘yes, you can help me, I have lost a ring’. They ask, ‘do you know where you lost it?’ and she answers ‘no, I don’t know where I lost it’. So then they ask, ‘well, why do you keep looking in this place?’ And she replies, ‘It is the only place that has a lamp post’.

In speaking about the media and its representation of Islam and Muslims, Professor Nanji commented that “Islam has been viewed, primarily under one lamp, and that lamp casts a very partial light. Therefore, the view that emerges of the Muslim world tends to be partial as well – it tends to be a view that sees Islam through the lens of conflict, chaos and violence.” This partial view of the Muslim world often becomes representative of Muslim activities in other arenas, influencing affairs on a global level. Furthermore, “this perspective misses both the immediate context of a particular situation or event and the commonality that is part of a shared historical experience between the West and Muslims over 1400 years.”

Professor Nanji also pointed out that “the media view of the Muslim world has tended to be very Arab-centric or Middle East-centric, often because the issues that are an obsession for the media in the Western world, focus on geopolitical affairs in that part of the world.” It is critical that we see beyond some of these stereotypes and stop seeing the Muslim world as monolithic. “We have to acknowledge the plurality of Muslims, their own diversity, the issues that they are struggling with on a day-to-day basis, reminding ourselves constantly that the majority of the billion plus Muslim community lives east of Cairo.”

Another part of the larger issue underlying the prevalent use of stereotypes about Islam and Muslims is that knowledge about Muslim civilization has often been relegated to the periphery of the curricula in state-sponsored schools and academic institutions. From an educational perspective, this marginalization reinforces the view of the Muslim world as being dominated by a “group of people who are responding in a very extremist manner to conditions in their own country”, and thereby represent a force of instability in the world.

A commitment to bringing the study of Muslim civilizations into the larger curriculum, on which The Institute of Ismaili Studies has been steadfastly working and which is now also being undertaken by Stanford University, is something, Professor Nanji urged, “needs to happen in the Muslim world as well. The sense of identity that most Muslims have of their own culture and civilization is then narrowed to the theological, and their Muslim heritage is seen as one expression of a particular part of a faith which is theologically or legally defined. Those aspects of Islamic civilization which have permeated into mainstream culture through science and the arts are lost in the present.”

Professor Nanji concluded his presentation by calling upon the delegates to build curricula into Journalism programmes “to train your colleagues and students to see the world through a lens that allows for a larger embrace of an increasingly diverse and complicated world. We as individuals who are interested in knowledge and its accurate portrayal have to embrace that complexity.”

The John S. Knight Fellowships for professional journalists at Stanford offer outstanding mid-career journalists the chance to broaden and deepen their understanding of a changing world, with the hope of improving the quality of news and information reaching the public through news media: print, broadcast and online. More than 700 journalists have held journalism fellowships at Stanford since the program began in 1966. Fellows have won numerous honours, including 26 Pulitzer Prizes and other major print and broadcast awards.