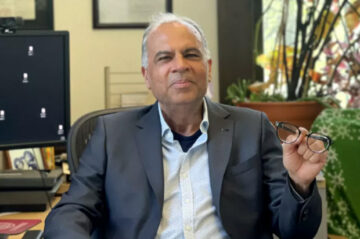

The central theme of Dr. Sajoo’s presentation was the role of maslaha or the ‘public interest’ in Muslim ethical reasoning, and how this has shaped particular choices in biomedicine, past and present. Five key narratives were offered to illustrate how maslaha allowed departures from traditional legal rules in order to serve a larger public interest. These involved decisions on organ donations, stem cell research, autopsies and dissection – followed by a final narrative on the classical emergence of maslaha itself as an avenue for social change in matters of public health. It usually comes as a surprise to western publics that supposedly ‘traditional’ societies such as Iran and Saudi Arabia have some of the most exciting and innovative programmes in health research, including on stem cell therapies for degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. The use of embryonic cells in such research has incurred strong opposition in several western countries on religious grounds. Muslim ethicists, however, have successfully addressed such concerns by balancing them against the public benefit derived from innovative therapies.

In similar vein, where traditional norms about preserving the integrity of the human body would have restricted such practices as the donation of kidneys and the conduct of autopsies and dissections, Muslim jurists have drawn on maslaha to encourage individual and community choices that better serve public health. Egypt’s al-Azhar University has been key to paving the way in this regard on national health policy, as have jurists in Iran and Saudi Arabia. Likewise, the Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi (Pakistan) has developed bioethical codes for clinicians that share the global bioethics emphasis on ‘beneficence’ and ‘avoiding harm’, yet do so from a robust Islamic perspective on public health innovation.

Dr. Sajoo’s final narrative, on the emergence of maslaha as a potent tool for social development, recalled the work of al-Shatibi (d. 1388) at a time when medicine was a field of unmatched advance across the Middle East. Thirteenth-century physicians such as al-Nafis and al-Dakhwar had built on the iconic Canon of Medicine (Qanun fi’l tibb) of Ibn Sina (c. 980-1037). In order to gain legitimacy in public health practice, medical breakthroughs had to be sensitive to the larger social milieu, including religious traditions. It was in this regard that al-Shatibi’s rational inquiry into the higher aims or maqasid of the shari’a allowed him to develop maslaha as a balance against legal rigidity – something that the noted theologian al-Ghazali (1058-1111) had begun. Much later, this spirit of ‘reason within faith’ was to serve as a vital instrument for Muslim modernity, and it continues to do so amid the difficult choices to be made today in biomedicine and applied ethics.