The latest IIS publication, Orations of the Fatimid Caliphs: Festival Sermons of the Ismaili Imams by Paul Walker, is the tenth publication in the Ismaili Texts and Translations Series. The book presents texts of several sermons from the Fatimid period, in Arabic and in English translation. Covering a period of about 100 years, these texts provide unique access to a key component of Fatimid public discourse.

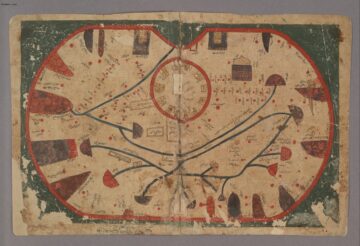

Contextualising the khutbas, the first two chapters of the book present the history of the Fatimid khutbas along with an insightful examination of their themes and rhetorical strategies. The Friday sermons in the medieval period of Muslim history usually indicated the political allegiance of the people. It was customary to mention in the khutbas the name of the ruling sovereign or the dynasty. Highlighting this importance of the sermons, the book begins with an account of the ‘Uqaylid ruler of north Mesopotamia, Qirwash b. al-Muqallad, announcing the transfer of his allegiance from the ‘Abbasid to the Fatimid caliphIn Arabic khalīfa, the head of the Muslim community. See caliphate., by way of the Friday khutba. Within this discussion of the general importance of sermons, the author discusses the sermons of the Fatimid caliphs. These were typically delivered twice a year on the occasion of the two Muslim ‘Id festivals. In the later Fatimid era, some of the Friday sermons during the month of Ramadan were also delivered by the caliph in specific mosques across the Fatimid territories.

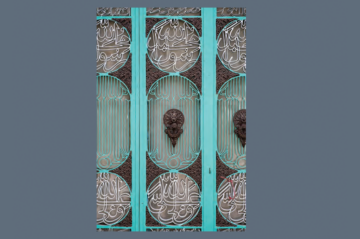

The varied religious affiliations of the populace in the Fatimid dominion meant that the caliphs took particular care to ensure that their khutbas could be understood by a broad audience. Language was thus critical in communicating political and religious ideas. The sermons usually followed a set pattern consisting of invocation to God, often using Qur’anic verses, praise and prayers for Prophet Muhammad, the reaffirmation of Fatimid lineage of the caliph to the Prophet through Imam Ali and FatimaDaughter of the Prophet Muhammad and his first wife, Khadīja bint Khuwaylid. Also wife of ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and mother of al-Ḥasan and al-Ḥusayn. al-Zahra, the Prophet’s daughter, and praise for succeeding imams. The sermons often included condemnation of the enemies of the FatimidsMajor Muslim dynasty of Ismaili caliphs in North Africa (from 909) and later in Egypt (973–1171) More with prayers for God’s support to defeat them.

In this way, the sermons provide significant insights into the nature of the wider socio-political context in which the Fatimids ruled. The sermons also contain several references to matters related to governance such as taxes, war and rights and duties of the sovereign. Moral advice formed yet another part of several khutbas. Often historical narratives, such as the struggles of the Prophet, were employed to illuminate the challenges the caliphs faced in their own times.

This book will be very useful for those interested in the history and traditions of the Fatimids. It provides interesting examples of imperial rhetoric as well as of public political discourse in a medieval Muslim context.