Farhad Daftary and Shainool Jiwa participated in a conference on ‘The FatimidsMajor Muslim dynasty of Ismaili caliphs in North Africa (from 909) and later in Egypt (973–1171) More and the Mediterranean’ organised by the Universita degli Studi di Palermo. The proceedings focussed on the social, cultural and political frameworks and institutions in the Muslim world as well as in the broader Mediterranean region during the Fatimid era.

Held from 3-6 December, 2008, the conference was organised under the patronage of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the Sicilian Region, The Institute of Ismaili Studies, and Fondazione Universitaria Italo-Libica (Italian-Libyan University Foundation). Dr Daftary delivered introductory remarks in the opening session and presided over the first session.

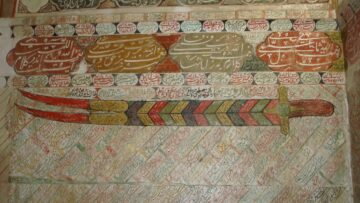

During the next session, Dr Shainool Jiwa delivered a paper on the ‘Historical representations of a Fatimid Imam-caliph: Exploring al-Maqrizi’s and Idris’ writings on Imam-caliph al-Mu‘izz li Din Allah’. She noted that although Taqi al-Din Ahmad b. Ali al-Maqrizi (845 AH/1449 CE) and ‘Imad al-Din Idris (d. 872 AH/1468 CE) were writing in the 15th century, almost three centuries after the Fatimid empire had waned, their writings assume primary source significance as, in constructing their narrative, they draw upon a spectrum of earlier North African, Egyptian and Iraqi sources, Sunni and Ismaili, which have not survived the vagaries of time and circumstance. Though contemporaneous, both authors, the first an Egyptian Sunni Shafi‘i jurist, the second a Yemeni, Tayyibi Ismaili Chief Da‘i, have significantly different interests and motivations when writing about the Fatimid era. This provided a relatively rare opportunity to study two discrete perspectives from which to understand and examine Fatimid historiography. An examination of their notions, purposes and expressions of history formed the focus of this paper.

The reign of the fourth Fatimid Imam-caliph, al-Mu‘izz li Din Allah [953-975 AH], in whose era Egypt was brought under Fatimid sway, thus transforming their North African state into a Mediterranean empire, has received significant attention from both al-Maqrizi and Idris. Thus, their writings on the life and times of Imam-caliph al-Mu‘izz provide an instructive case-study on the focus, scope, purpose and perimeters of what constitutes historical narratives in Fatimid historiography and, by extension, in formative Muslim historical writings. Dr Jiwa postulated that al-Maqrizi strives to present what he considers to be accurate knowledge, through a reasoned examination of the source materials available to him. Adopting what would today be considered an empiricist, Rankean approach; he notes an expressed preference for sources that are in close spatial and geographic proximity to the events they are describing. For ‘Imad al-Din Idris, on the other hand, the purpose of recording terrestrial history is to faithfully understand and document the unfolding of a primordial divine purpose within the Tayyibi Ismaili doctrinal and cosmological structure of the universe. Hence, while the recording of human engagements is necessary and important, essentially it serves a larger, symbolic ethos and function. The paper, therefore, argued that for Idris the defining paradigm of the acceptability of a source was whether it resonated with this worldview, regardless of its eastern or western, Sunni or Shi‘i provenance. Consequently, the Itti‘az of al-Maqrizi and the Uyun of Idris complement and supplement each other in providing as historically accurate and as symbolically representative a rendering of the Fatimid weltenschaung as is possible within our current purview of primary sources.