Dr Shiraz Thobani, a Research Associate with the Department of Curriculum Studies at the Institute, has co-edited a new publication with Dr Gerdien Jonker, entitled Narrating Islam: Interpretations of the Muslim World in European Texts. Dr Jonker is affiliated with the Georg-Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research in Braunschweig, Germany.

The series of articles in this publication were first presented by European scholars at an international conference and workshop on the subject which took place in 2006 and 2007. The articles explore both the history and contemporary representations of narratives about Islam and Muslims, as reflected in European school textbooks.

In this context, Muslims have often taken the role of the ‘other’ during the last 500 years of European history, that is, from the Reformation up to the 21st century. In each region, the role of the ‘other’ is linked to safeguarding their indigenous, cultural and political frameworks. The militarily and culturally superior Ottomans, along with other Muslim cultures at Europe’s margins, were one of the catalysts for European self perception. Thus, these narratives lead to increased collective identity and group cohesion.

The editors’ hypothesis is that textbook narratives on Islam have their roots in ideas that are still one of Europe’s basic identifiers of belonging and not belonging. The majority of European school textbooks share basic features such as ‘the life of Muhammad’ or ‘the Crusades’. Drs Thobani and Jonker argue that these narratives have been fixed over a long period of time and can only be understood by looking at the longue durée of European historiography, following ideas from Fernand Braudel’s seminal work.

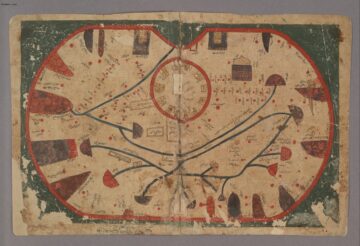

Dr Thobani, in his concluding chapter, called Peripheral vision in the national curriculum: Muslim history in the British educational context, brings the discussion right up-to-date. The chapter deals with the role of the UK national curriculum in promoting cultural diversity and civic identity in the context of Muslims and Islam. Even today, the Islamic world is seen as an essentially bounded entity, centring on the Middle East. Other areas, such as North Africa, Central Asia or India, are only mentioned in passing.

The predominant emphasis on the texts examined by Dr Thobani is on Muslim religious and political, rather than socio-cultural history. “The Muslim ‘world’… is distanced by being neatly separated from Europe, embedded in a medieval age and therefore having little if any engagement with modernity, and cast as confrontational through conflictual episodes such as the Crusades” (p.249). Dr Thobani traces these perspectives back to an Orientalist discourse.

A better alternative, Dr Thobani suggests, would be to discuss the richness of Muslim civilisation and its interdependence with other civilisations as well as the century-long history of Muslims within Europe. The textbooks should also be brought up to the present day: “It is vital that the peripheral gaze be led to focus also on the encounter between Muslim societies and European nations in the colonial period and in recent times” (p.252).

While textbook narratives of cultures are often based on ideas that reach long into the past, they seek to shape young readers’ futures. Thus, in a changing post-colonial world where old divisions and certainties are being revised, this volume sheds a welcome light on a previously neglected area of study.