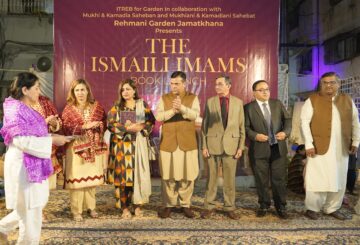

Two IIS publications, Towards a Shi‘i Mediterranean Empire and The Founder of Cairo, both by Dr Shainool Jiwa, were launched at an event held in Mumbai, India, on February 14, 2014. Dr Shainool Jiwa, a specialist in Fatimid history, spoke at the event about her two latest works in a discussion with Anisa Virji, a GPISH alumnus and a member of the Ismaili Tariqah and Religious Education Board for India. Their dialogue covered the vast Mediterranean empire of the Fatimid Imam- caliph al-Muizz, whose reign spanned North Africa, Syria and Egypt in the 10th century CE.

Imam-caliph al-Mu‘izz founded the city of Cairo in 969 CE, having extended Fatimid rule across the Mediterranean from North Africa to Egypt and Syria, through a series of strategic and diplomatic initiatives, including the fostering of ties with Egyptian notables through the Ismaili da‘wa. Under the Fatimids, Cairo became a vibrant cosmopolitan metropolis contributing to the cultural and intellectual efflorescence of the region alongside Baghdad, Constantinople and Cordoba.Imam-caliph al-Mu‘izz articulated the principles of inclusive governance in the Aman document, the Guarantee of Safety, issued to the people of Cairo comprising at the time of Muslims of Sunni and Shi‘i traditions, Christians and Jews. In that document, he proclaimed:

I guarantee you God’s complete and universal safety, eternal and continuous, inclusive and perfect, renewed and confirmed through the days and recurring through the years, for your lives, your property, your families, your livestock, your estates and your quarters, and whatever you possess, be it modest or significant.’ (p. 17, Towards a Shi‘i Mediterranean Empire)

From this commitment rose a city built around a splendid mosque, Al-Azhar, which quickly established itself as a centre of intellectual and cultural activity along with the Dar al-Hikma, founded in 1005 CE, that drew scholars from around the Muslim world. The Fatimids appointed administrators from various religious traditions and ethnic affiliations, rewarding competence with senior positions, thus drawing talent from the varied spectrum of Egyptian society.

In recent years, many parts of the Muslim world have been rent with uprisings and civil conflicts, as they grapple for a suitable model of good governance and inspiring leadership. In this context, the Fatimid model of inclusive governance that Dr Jiwa presents – one that enabled them to rule as a minority over diverse lands for over two and a half centuries – acts as an interesting example from within Muslim history.

Two 15thcentury scholars: al Maqrizi (d. 1442 CE), an erudite Sunni scholar from Egypt; and Idris Imad al-Din (d. 1468 CE), the Chief da’i of the Tayyibi IsmailisAdherents of a branch of Shi’i Islam that considers Ismail, the eldest son of the Shi’i Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 765), as his successor. in Yemen, wrote extensively about the vibrant Shi‘i Mediterranean empire which Imam-caliph al-Muizz established. From two very different perspectives, they recount the milestones of Fatimid history and thought, including the spread of the Ismaili dawa, their diplomatic initiatives, thriving trade, pluralistic attitudes and intellectual debates and exchanges, which characterised this period.

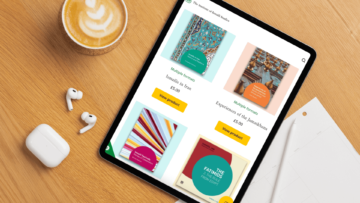

Dr Jiwa has translated, from Arabic into English, two of the seminal works of these scholars, both of whom draw upon a range of primary sources, to portray a comprehensive representation of the Mediterranean milieu in which the Fatimids reigned. Several of the sources cited by them are lost to us today, making the works of al-Maqrizi and Idris indispensable to our understanding of the Fatimid period.