It is with deep sadness that the IIS announces the untimely loss of Dr Janis Esots, colleague and esteemed scholar.

Born in Jaunpiebalgas, Latvia, in 1966, Janis received his first degree in 1991 from the prestigious Moscow Institute of Literature (Department of Translation, Persian language group) and obtained his doctorate in 2007 from Tallinn University, Estonia, with the thesis: ‘Mullā Sadrā’s Teaching on Wujūd: A Synthesis of Philosophy and Mysticism’.

Janis joined the IIS in 2013 as a Research Associate in the Shi‘i Studies Unit of the Department of Academic Research and Publications (DARP). He was also concurrently Associate Professor at the Department of Asian Studies at the University of Latvia, Riga, having assumed that position in 2010. As well as these institutions, Janis had also previously held lectureships at the Islamic College in London and the Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

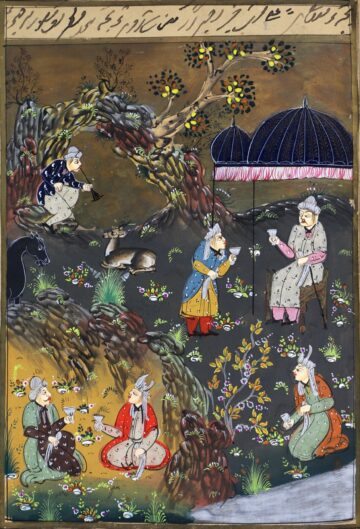

Aside from his native Latvian, Janis enjoyed a true mastery of English, Russian and Persian, to the extent he was able to author monographs and edit complex philosophical texts in these three languages, as well as translate between them. His command of Persian was so well recognised in his native Latvia that once, during the visit to capital Riga by the then Iranian President, Mohammed Khatami, he was invited to act as an official interpreter. He also knew classical Arabic, classical Greek, Latin, French, German and Turkish. His background and his command of so many languages afforded him the rare ability of working across a broad range of international academic networks—particularly those of Russia, Iran and Europe—and he undoubtedly helped to forge connections between different traditions and scholarly circles. Perhaps this is best illustrated by his Ishraq: Islamic Philosophy Yearbook, the trilingual journal published in Moscow which he founded in 2009. A collaboration between the Institute of Philosophy in Moscow, and the Institute of Philosophy and the Ibn Sina Islamic Culture Research Foundation (both in Tehran), its editorial board boasts thirty scholars of global renown in the fields of philosophy and mysticism.

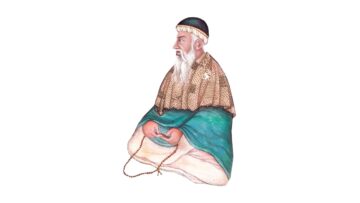

For Janis, the Persian language was not just an academic endeavour, he also delighted in its poetic wordplay and elaborate conventions. In the words of Professor M. A. Amir-Moezzi: ‘What struck me about him, apart from the contrast between his extreme gentleness and his Baltic robustness, was his way of speaking Persian. He spoke the delightfully antiquated Persian of traditional scholars, old hommes de lettres and dervishes’. Janis would often sign his emails with the self-deprecating epithet ‘haqir’, meaning ‘the wretched or lowly one’, while addressing others with praiseworthy titles that emphasised their status and learning.

Aside from the language, Janis also had a deep appreciation for other aspects of Persian culture, particularly its classical music. His friend Mahyar Alinaghi recalled that Janis had been to many international concerts of Iranian music, particularly those of Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, and had a deep knowledge of Khorasan’s maqami musical traditions. He had also made personal contact with Maestro Nurmohammad Dorpour, one of the last bards of KhorasanThe northeastern region of early Islamic Persia, immediately south of Transoxania and west of Badakhshan. and a Sufi master of the Naqshbandi order.

At the time of his passing, Janis was working on a number of IIS publication projects which he pursued with his usual dedication and commitment. The first of these was The Renaissance of Shīʿī Islam in the 15th-17th Centuries: Facets of Thought and Practice, the edited proceedings of the international conference he organised at the IIS in October 2018. He was also working on a monograph, Patterns of Wisdom in Safavid Iran: The Philosophical School of Isfahan and the Gnostic of Shiraz, and updating, with Farhad Daftary, the second edition of Historical Dictionary of the IsmailisAdherents of a branch of Shi’i Islam that considers Ismail, the eldest son of the Shi’i Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 765), as his successor.. In addition, Janis was managing editor of Encyclopedia Islamica, a project for which he also made contributions as author and translator.

Janis had also published a significant number of scholarly editions, translations and commentaries of Islamic philosophical and esoteric texts, as well as articles in journals and edited collections. His authoritative status was such that he was often invited to write encyclopaedia articles and book reviews. Janis was also a member of various editorial boards, had won awards and had been the recipient of a number of research grants. His long-standing friend and associate, Professor Carmela Baffioni, describes him as someone of ‘vast knowledge and endowed with great acumen—he was a tireless worker and a tireless traveller. I believe that Janis cannot be replaced by a single person in all his many scientific endeavours, but I am sure that we will all try to work together to carry on his legacy’. The IIS’ co-director, Dr Farhad Daftary, described Janis as a rare scholar with many skills and accomplishments, akin to the orientalists of an earlier age. He said:

‘I was always amazed by his knowledge of Islamic traditions as well as the Persian language. His absence will be very noticeable for all of us at the IIS’.

As a complement to his work, Janis was also a keen traveller and enjoyed attending conferences to present academic papers. In recent years he had travelled to Dushanbe, Khorog, Marrakech, Isfahan, Berlin, Tehran, Paris, Palermo, Venice, St Petersburg, Baku and Kalamazoo, to name but a few of his destinations. His friend Roy Vilozny recounts: ‘Travelling was one of Janis’ greatest passions and, as in other domains, he totally immersed himself in it. Shortly after I landed for the first time in Baku, Azerbaijan, the starting point of one of the journeys on which I embarked with Janis, one of his friends told me: “You don’t realise how lucky you are. You came here with the key to Azerbaijan – Janis Esots”. Thanks to Janis, Azerbaijan was revealed to me in a very special way, accessible only through his mediation and generous initiation. As years went by, I realised that Janis was not only “the key to Azerbaijan”. Wherever on the globe I met him, whether in Europe, Central Asia, the Caucasus or Russia, he was key to a unique, intimate acquaintance with the local religion, history, literature and poetry, politics, food and drink and, above all, with people who deeply loved him and highly appreciated him’.

Janis was always quiet and courteous, with a diffident and humble manner that belied his elevated level of intellectual learning. Although he did not openly profess any religious affiliation, he evidently had a deep affinity with Sufism and conducted himself with characteristic adabA word of many meanings usually connoting courtesy, etiquette, rules and manners, civilisation, culture and literature. (formal correctness, etiquette). He engaged in acts of great kindness and had an exceptional generosity of spirit. Just one example of this generosity is recounted by Roy Vilozny: ‘When, on another occasion, after landing in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, Janis found out that his luggage was missing, the only thing he was really upset about was that the medicine he had brought from London to a parent of a friend would not reach its destination in Badakhshan. A week or so later, when we were already back in Dushanbe from our trip to Badakhshan, the luggage was traced. The first thing Janis did, even before putting on a new shirt, was to find a way to send the medicine safely to his friend’s parent. Janis was a friend you could always count on and his many friends worldwide, who knew it, never hid their affection for him’.

Indeed friendship, or suhba as he termed it, was a major source of joy for Janis. As his colleague and friend, Dr Fârès Gillon, describes:

‘Not only did Janis have many friends, but he practiced the art of friendship to the highest degree. As a friend of Janis, one could measure the full extent of the generosity of someone who would spare no effort to help, yet always presented his willingness to help as a duty: la shukran ‘ala al-wajib, “it is not necessary to thank for something that is due”, he would say’.

In conversation, Janis was a man of few words but his powerful baritone voice conveyed both weighty ideas and an infectious chuckle. IIS Senior Research Associate, Dr Toby Mayer, remarks: ‘Janis was outwardly reserved and seemed contentedly solitary, but as soon as you engaged with him he would regale you with his dry sense of humour, and his interest in topics beyond Muslim intellectual history, such as Baltic paganism. He spoke to me of his early enthusiasm for archaeology, expressed in a childhood project to excavate tunnels under the family home in Latvia, which was put a stop to because of the danger caused to the house’s foundations. He was amazingly generous, both with sharing his copious philosophical expertise and also in bringing back gifts of books, wine and delicacies for friends and colleagues whenever he returned to London from his travels’.

Janis enjoyed nature and particularly walking holidays; he would sometimes, apparently quite spontaneously, take himself off on adventures to places such as the Scottish Highlands. It was sadly on one such solitary walking holiday in Polperro, Cornwall, that on June 12th he suffered a medical emergency and help was unable to reach him in time.

Janis is survived by relatives in Latvia and Australia, and is fondly remembered by a large, international community of people who can say they had the privilege of calling him a friend.