Ismaili Festivals: Stories of Celebration by Dr Shiraz Kabani is the first title in the IIS’s new Living Ismaili Traditions (LIT) series. The book is a unique and personal account of festivals and traditions from the author’s own lived experience as an Ismaili. Here Dr Kabani—who heads the IIS’s Department of Community Relations—reflects on the aims of the series, who it is for, and the importance of storytelling.

Please could you tell us about the genesis of the Living Ismaili Traditions series?

For a number of years the Institute has been working on developing publications that will appeal to individuals who are not academics in the field of Islamic Studies, where we could bring together a lot of the research and scholarship that has been undertaken by the Institute. The Living Ismaili Traditions series was conceptualised specifically for the Ismaili community to address some of the issues of contemporary relevance to the community. And given that most communities are made up of people who have shared narratives, shared stories, shared festivals, we thought that the first book could take this up as a subject to communicate certain important ideas to the community.

There is much in Ismaili history, particularly in terms of the recent past—stories of migration, stories of settlement, how communities in different parts of the world have developed—that has not been talked or written about, at least not in very accessible language. Unless they are scholars in the field of Ismaili studies, many in the community are not familiar with parts of the history of the community, except what is commonly known. And so it is our hope that these books will shed light on important episodes and personalities in Ismaili history, so that the Jamat is better aware and understands its own past and present better.

Can you tell us about the role of storytelling in Ismaili Festivals: Stories of Celebration?

Anthropologists tell us that human societies have told stories to each other since time immemorial. I remember reading a research study where students in a classroom were shown certain geometrical figures as part of a film, and they were asked to make sense of it. Every single person, except for one individual, made a story out of those patterns. What that tells us is that we tell stories to make sense of things. We are meaning-makers by nature, and we need to tell stories to ourselves, to see patterns, because that helps to make sense of the world around us.

In the book you will find three different types of stories. First, stories that are closely associated with the festivals have been included. So, for example, the story of Prophet Abraham and his son, and their sacrifice, is associated with Eid al-Adha and is therefore narrated. The second type of stories are those that have come down to us in history, mostly through oral tradition. These are stories that you find in the Hadith, stories that you find in the Mathnawi of Rumi, for example. These were selected on the basis of their contemporary relevance. The third are stories from my own life, some funny, some sombre, but events that taught me lessons that may be of relevance to the readers of the book.

Can you give us a taste of one of the festival experiences you write about in the book?

In the chapter on Imamat Day, which is the celebration of the anniversary of the present Imam’s accession to the Imamat, I describe celebrations in London. Beyond the gatherings in Jamatkhanas, on this occasion there are usually exuberant celebrations where a large number of IsmailisAdherents of a branch of Shi’i Islam that considers Ismail, the eldest son of the Shi’i Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 765), as his successor. get together in a spirit of joy and camaraderie. During those celebrations, there are certain songs that are sung and dances that are performed in large groups. In the book, I have tried to describe that scene and then explore the purpose and meaning of the celebrations. In this context, I have also discussed how such celebrations are frowned upon in some Muslim interpretations and why this is not perceived as an issue amongst the Ismailis.

What are some of the ideas you explore in the book?

The first idea that I’ve tried to communicate in the book is about diversity and its beauty, for people to understand the astonishing diversity that exists in human societies, more specifically in the Muslim world, and also amongst Ismaili communities. The second, related idea is that, within this diversity, there is also a unity. There is much among the Ismailis in terms of their culture, their festivals, and their stories that they share with other traditions of Muslims, and indeed, with other religious communities. And the third idea is to reinvigorate this notion of storytelling, which is an art that, in my view, we seem to be losing. And I’m hopeful that when people read this book, they will be encouraged and motivated to read more of the stories, but also to tell more stories among themselves.

Who is the book for?

If you are someone who wants to know something more about the Ismaili tradition, its cultures, its stories, its festivals, then this book is for you. If you are faced with questions about your tradition and are looking for ways to respond, then this book is for you. I’ve specifically written it for people who don’t have academic expertise in the field of Islamic Studies. Wherever there is a complicated idea, I’ve provided contemporary examples for readers to understand those ideas. So, if you feel that you want to better understand your own Ismaili tradition, then this book is for you.

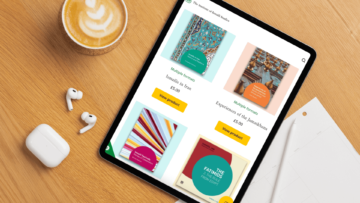

Ismaili Festivals is available to order from local ITREBs.