The Ismaili Texts and Translations series aims to produce critical editions of Ismaili texts, together with English translations and contextualising introductions, which are essential for further progress in the field of Ismaili studies. In this interview the series editor, Dr Orkhan Mir-Kasimov, gives an insight into the series’ scope and aims, the importance of critical editions, and future plans for Ismaili Texts and Translations.

Please could you tell us about the genesis and scope of the series?

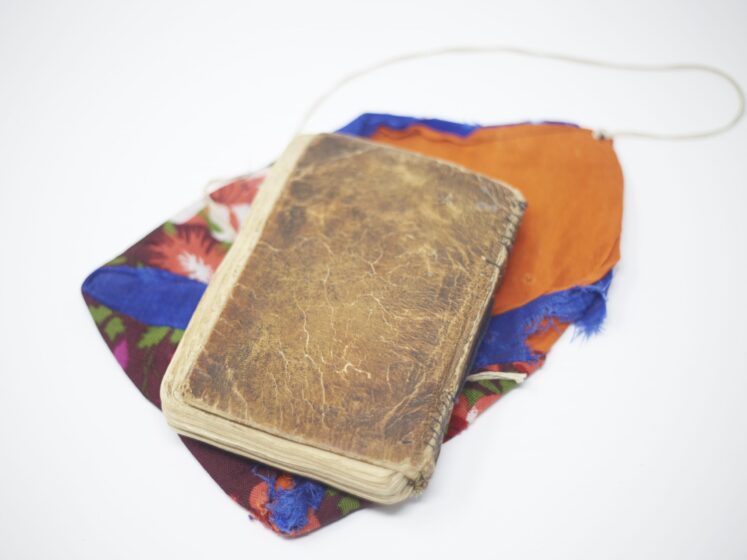

The first publication in the Ismaili Texts and Translations series was in 2000. Since then, there have been 26 books published in the series. The books in the series usually contain a critical edition of a source text and an annotated English translation. They cover a large number of subjects, including Ismaili history, doctrine, theology and law. Until now, there has been a clear focus on Fatimid history and doctrines. This is understandable given the importance of the Fatimid Empire in Ismaili history. The series also includes several books on the Nizari and Tayyibi branches of Ismailism, and we are committed to creating a diversified representation of various Ismaili branches and intellectual tendencies in future. Some of the source texts are selected from unpublished manuscripts preserved in the IIS’s Ismaili Special Collections: one aim of the series is to make these more available and readable.

Please could you tell us a bit about the two most recent additions to the series, Affirming the Imamate by Professor Wilferd Madelung and Dr Paul Walker, and Command and Creation by Dr Daryoush Mohammad Poor?

Affirming the Imamate includes a critical edition and translation of two important early Fatimid texts, which were until now virtually unknown, and which deal with the Ismaili theory of the Imamate.

Command and Creation is the text of the prominent Muslim thinker Al-Shahrastani which, among others, brings some new evidence on the affinities between Shahrastani’s thought and Ismaili doctrines, and more specifically on Shahrastani’s possible input in the development of the Nizari Ismaili doctrines. Those interested in this book can now watch a recording of the book launch with the author, Dr Daryoush Mohammad Poor, and Dr Toby Mayer, who has published another book on Sharastani, Struggling with the Philosopher, in the series.

What are the aims of the series?

The general aims of the series are to promote the knowledge and study of Ismaili intellectual heritage and, of course, make Ismaili texts available to the Ismaili community, to the broader readership, as well as to scholars.

The unpublished Ismaili manuscripts collected and preserved in the Ismaili Special Collections Unit are an important resource for the series, and one of our goals is to increase the visibility of our collections and their availability for scholarly research and a broader readership through the publication of critical editions and translations in the series.

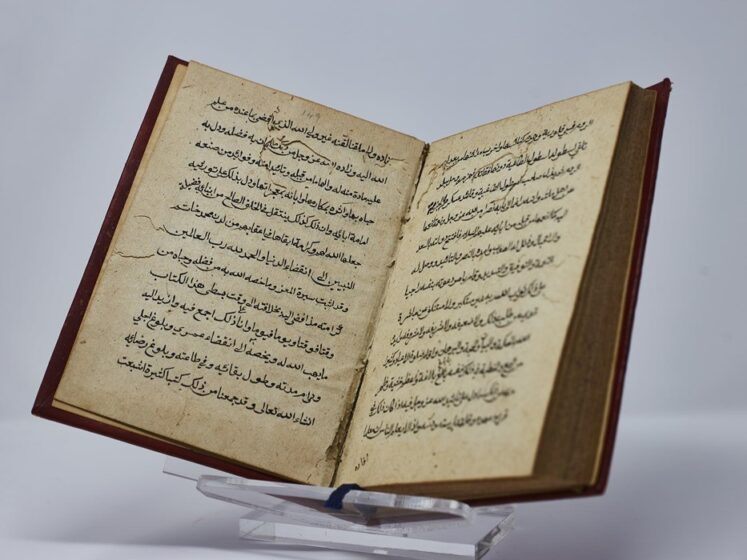

Critical editions are important because, in medieval times, most books circulated in the form of manuscripts, meaning that they were made by scribes. It is relatively rare, especially for the older texts, that we have an autographed copy of a manuscript written by its author. Of course, scribes are human beings, they made mistakes, added comments to the original text and removed things. Then other scribes would make a copy and could make other alterations. So the problem when we deal with these manuscripts is to see what relation the copy has with the original text, and this is exactly the issue that the critical edition addresses. When scholars prepare a critical edition, they try to consult and to compare as many manuscripts of the given text as possible, to see if they can identify any scribal mistakes or other alterations that the text might undergo in the process of transmission. The goal is to make the reader aware of the differences between the manuscript copies of the same work, and to try to reconstruct as much as possible the text closest to the original copy. Dr Wafi Momin’s recently published edited volume Texts, Scribes and Transmission addresses this manuscript tradition directly.

Most of the books in the Ismaili Texts and Translation series also contain an annotated English translation of the text. So if the critical edition is probably more for the scholarly community, the English translation makes the texts—this Ismaili intellectual heritage—accessible to a much broader readership. But just as a critical edition is more than just a facsimile copy of the manuscript, a scholarly translation of a medieval text is more than just a translation. Any translation necessarily contains an element of interpretation, but in the case of medieval texts the task of translation also involves an in-depth understanding of original and sophisticated theories, expert knowledge of their cultural, historical and intellectual context, and the challenge of expressing the medieval concepts and technical vocabulary in modern English, making them accessible for the reader.

What are some other series highlights?

The series with its focus on Ismaili intellectual heritage occupies a clearly defined place in the landscape of publications related to Islamic studies. All the books in the series are important and it’s very difficult to highlight one of them over another. But of course, the series contains books on some prominent figures of Ismaili history and philosophy, such as Al-Qadi al-Numan, Nasir al-din Tusi, Nasir Khusraw and Al-Shahrastani. These authors are prominent figures not only of Ismaili but also more generally of Islamic intellectual history.

What are your plans for the series? Can you tell us about any upcoming titles?

We currently have three books which are at different stages of preparation, and they cover Nizari, Fatimid and Tayyibi branches of Ismailism.

As mentioned, the previous publications in the series have been focused on the Fatimid period, Fatimid authors or Ismaili authors writing on Fatimid history. In terms of plans, we would like to look at progressively diversifying the branches of Ismailism that are represented in the books published in this series.

In order to be able to do this, we have started working on different interconnected points. One of them is consolidating the series’ documentation and processes, including clear guidelines for authors and peer reviewers, and close collaboration with copy editors. We want to make sure that our processes are really robust, that the series maintains its strong reputation in the field and is attractive to the authors. The scholarly quality control, including the review and feedback process, is particularly important. In addition to the editorial review, we obtain review reports from at least two independent external scholars with the proven expertise in the required area of study on every typescript that is submitted for the series. We are working very closely with our publications department to consolidate these procedures and to make sure that our publications meet the highest academic standards.

We also closely collaborate with our Ismaili Special Collections Unit in order to research and identify the Ismaili manuscripts in our collections which would be interesting for a critical edition and translation, and also to develop collaborations with scholars who previously worked with manuscripts in ISCU’s collections.

We are also working on broadening and widening our network of scholars who want to collaborate with us, either as the authors of the critical editions and translations or as peer reviewers. This is important because critical editions and translations of medieval manuscripts require a very specific set of skills, including relevant linguistic skills, expert knowledge of the subject, and experience of critical editions of medieval manuscripts. A capacity to identify and attract scholars with this required expertise is therefore vital to ensure that we have high-quality editions and translations.