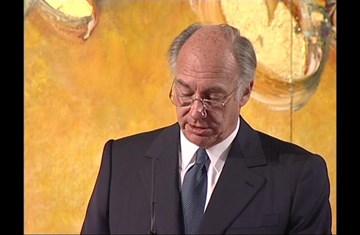

Address by His Highness the Aga Khan at the 25th Anniversary Graduation Ceremony

Address by His Highness the Aga Khan, IIS 25th Anniversary Graduation Ceremony

At this graduation ceremony which took place at Le Meridien Grosvenor House Hotel in London on the afternoon of October 19, 2003, fifteen Members of the Class of 2004 and 180 alumni of the Institute’s varied programmes were honoured. In attendance were over 1,600 guests including the Chairman of the Institute’s Board of Governors, His Highness the Aga Khan.

Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim

Distinguished guests, The faculty, staff and students of The Institute of Ismaili Studies, ladies and gentlemen,

It gives me immense happiness to be present at this graduation ceremony of the Programme in Islamic Studies and Humanities at the Institute of Ismaili Studies. I genuinely share the joy and pride of everyone associated with this programme, and particularly the graduands. Many of you, with your prior qualifications, have the capacity to pursue different paths in life but, by joining this programme, you have opted to undertake a systematic study of your heritage. I hope that you will feel that this choice has not been in vain, and that what you have learnt will be a source of inspiration and satisfaction in your life, whatever professional path you follow. The studies you have undertaken should, I believe enable you to play a role in helping to address the issues of contemporary relevance to Muslim societies.

The Muslim world today is heir to a faith and a culture that stands among the leading civilisations in the world. The revelation granted to the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) opened new horizons and released new energies of mind and spirit. It became the binding force that held the Muslims together despite the far-flung lands in which they lived, the diverse languages and dialects they spoke, and the multitude of traditions – scientific, artistic, religious, and cultural – which went into the making of a distinctive ethos. This message is still potent in the Muslim world today, although it is sometimes clouded, distorted and deformed by political interests and by struggles for power over the minds and hearts of people. There are attempts at transforming what are meant to be fluid, progressive, open-ended, intellectually informed, and spiritually inspired traditions of thought, into hardened, monolithic, absolutist and obscurantist positions. Yet there are many across the length and breadth of the Muslim world today who care for their history and heritage, who are keenly sensitive to the radically altered conditions of the modern world. They are convinced that the idea that there is some inherent, permanent division between their heritage and the world of today is a profoundly mistaken idea; and that the choice it suggests between an Islamic identity on the one hand and on the other hand, full participation in the global order of today is a false choice indeed. They seek for ways in which their societies may benefit from the intellectual and material fruits of modernity, while remaining true to their distinctive moral, spiritual and cultural heritage.

Yet it is not a simple matter for any human society with a concern and appreciation of its history to relate its history and its heritage to its contemporary conditions. Traditions evolve in a context, and the context always changes, thus demanding a new understanding of essential principles. For us Muslims, this is one of the pressing challenges we face. In what voice or voices can the Islamic heritage speak to us afresh - a voice true to the historical experience of the Muslim world yet, at the same time, relevant in the technically advanced but morally turbulent and uncertain world of today?

One of the challenges that has concerned me over many years, and which I have discussed with leading Muslim thinkers, is how education for Muslims can reclaim the inherent strengths that, at the height of their civilisations, equipped Muslim societies to excel in diverse areas of human endeavour.

Clearly the intellectual development of the umma, is, and should remain, a central goal to be pursued with urgency if we wish the Muslim world to regain its rightful place in world civilisation. Today, any reasonably well-informed observer would be struck by how deeply this brotherhood of Muslims is divided. On the opposite sides of the fissures are the ultra-rich and the ultra-poor; the Shiʿa and the Sunni; the theocracies and the secular states, the search for normatisation versus the appreciation of pluralism; those who search for and are keen to adopt modern, participatory, forms of government versus those who wish to re-impose supposedly ancient forms of governance. What should have been brotherhood has become rivalry, generosity has been replaced by greed and ambition, the right to think is held to be the enemy of real faith, and anything we might hope to do to expand the frontiers of human knowledge through research is doomed to failure for in most of the Muslim world, there are neither the structures nor the resources to develop meaningful intellectual leadership.

You will forgive me, I hope, for presenting to you such a grey picture of where we in the umma stand today, but, unless we have the courage to face unpleasant reality, there is no way that we can aspire realistically to a better future.

Several days ago, at a meeting of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference in Malaysia, it was pointed out that the only way the umma can work its way out of its present sad state is to harness the intellect. I deeply share this conviction, but three immediate questions follow: How do we foster intellectual development in the umma? In what areas of human knowledge should we seek to lead? And where should we source our education?

It is in an endeavour to address such critical questions relating to education that the Ismaili Imamat has undertaken a number of initiatives.

The Aga Khan University was founded in Pakistan in 1983 and today, its academic activities radiate into Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and the United Kingdom. In 2001, an international treaty between the Ismaili Imamat and the Republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan resulted in the establishment of the University of Central Asia, which aspires to impact the intelligentsia of the whole mountainous region of Central Asia with campuses in these countries. This University will study developmental issues specific to high mountain societies, while also offering courses in the humanities to promote respect for cultural pluralism and strengthen the foundations of civil society.

Last year, I took the decision to launch a network of Schools of Excellence in the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia and Southeast Asia, with the aim of educating young men and women up to the highest international standards from primary through higher secondary education. It is my hope that, in due course, these schools will be located in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Madagascar, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, Syria and, in due course, Mali. Students and faculty will be encouraged to move through this school system which, of course, will need to be residential, so that the graduates have been exposed to different social, ethnic and religious environments; have become bilingual and, perhaps, trilingual; and will be equipped to lead in the professions in the societies in which they decide to establish themselves, whether or not they go to the best universities in their own countries, or the best universities in the Western world. The students’ areas of specialisation will be in the fields of knowledge most required for the development of their societies, home countries and regions, but they will also have a strong grounding in the humanities and, in particular, the cultures of the Muslim world. They will be fully qualified in the use of modern information technologies, and thus wherever they are, they will have easy and quick access to the world’s most sophisticated knowledge bases, wherever they may be. The graduates’ beliefs, practices, ethics and social norms will be those of their own societies, and their own cultures, and their value systems will be rooted in their own histories, and their own arts.

As these young men and women grow into leadership positions in their own societies, including teaching future generations through their schools and universities, it is my hope that it will be these new generations of our intelligentsia, who, driven by their own knowledge and their own inspiration, will change their own societies and will gradually replace many of the external forces who today appear, and indeed sometimes seek, to control our destinies. These young men and women will become leaders in the institutions of civil society in their own countries, in international organisations, and in all those institutions, academic, economic and others, which cause positive change in our world.

As more nations develop increasingly multi-cultural, rather than uniform or monolithic profiles, and as the process of globalisation continues apace, educators are confronted by the challenge to provide to the mainstream population of their society, an informed understanding of the culture and history of minorities domiciled in their midst, as well as other major civilisations beyond their shores.

It must be said that, in this respect, most of the countries of the West have been staggeringly slow to face up to this challenge, at least as far as Islam is concerned. The media and some opinion-leaders tend, if not to actively perpetrate clichés and stereotypes, show a lack of anything like a nuanced knowledge or appreciation of the traditions of the Muslim world. School curricula in the humanities and social sciences are often formulated as if Islam did not exist or was not the religion and culture of a substantial portion of humanity. As a result, even a distant acquaintance with the world of Islam is nearly totally absent from the general knowledge of Western society. Undergraduate courses in universities, when describing and evaluating major achievements in the arts, sciences, philosophy, religion and ethics, refer almost exclusively to figures in European or American history. Indeed, Islamic studies have been mostly relegated to the minute and often-unheard minority of academic specialists in Western universities.

In an effort to address these concerns, the Aga Khan Development Network is working closely with a number of leading North American Universities and State educational authorities with a view to developing and implementing appropriate school curricula on Islam. In a related, though separate, initiative, the Ismaili Imamat is currently in the process of establishing a museum in Toronto as a significant resource for disseminating information and education about Islam’s vast and varied heritage, and its interface with the many cultures in which it has evolved.

These and other initiatives, including The Institute of Ismaili Studies, are a continuation of the historic Ismaili tradition to promote knowledge and learning, in line with the great ideals of Islam.

To the graduands, past and present, I convey my very warm congratulations on this special day. I also wish you well in whatever careers you now choose to pursue. Among the options that you may consider are, for example, teaching at the Aga Khan University, particularly at the College of Arts and Sciences when it opens its doors Insha’Allah in 2007, at the University of Central Asia or at the Centres of Excellence that the Aga Khan Education Services are currently in the process of establishing. You may also find interest in the major teacher education programme on which the Institute of Ismaili Studies is about to embark, in the context of the secondary level curriculum that has been developed for the Jamat.

It is my hope and prayer that the education and training that you have acquired will enable you to assume positions of leadership in your communities, countries and even beyond. I believe that your continuing relationship and dialogue with the Institute will enrich your role as potential agents of change, while also extending to the Institute the benefits of your experiences and insights. This partnership can ensure that you are well placed to contribute to the development and growth of future generations of our intelligentsia, so that we strengthen our own capacity to determine our destiny.

Thank you.