The Voices of History: From London to Zanzibar

In this episode we hear from Professor Farouk Topan, one of the founding faculty members of The Institute of Ismaili Studies and a renowned scholar of Swahili literature. Professor Topan shares his experience of growing up in cosmopolitan Zanzibar and describes his participation in the Takht Nashini accession ceremony of His Highness the Aga Khan to the Ismaili Imamat in Dar es Salaam. He also recounts the formative days of The Institute of Ismaili Studies in London in the 1970s and 1980s.

Rizwan Karim, coordinator of the Oral History Project in the Ismaili Special Collections Unit, sat down with Professor Topan for an exclusive interview.

When Sir Tharia Topan (Farouk Topan’s grandfather) came to Zanzibar from Gujarat around 1836, he was a successful merchant with a reputation for honesty and integrity. His trading network extended from the east coast of America to southeast Asia, and he owned several ships and dhows. He also held a prominent role in the councils of Sayyid Barghash, the Sultan of Zanzibar.

“By the time he died, he had become quite an entrepreneur, he was quite well known,” remarks Professor Topan. “He was knighted because he had assisted in the abolition of slavery. He was knighted when he had gone back to Bombay…he came from Kutch and then he went back and settled back in Bombay: that's where he died. So, he was quite a well-known figure who also played quite a significant role in the Jamat, both in Zanzibar and I think also in Bombay.”

Sir Tharia Topan was also a philanthropist in his local community and helped fund the establishment of a medical dispensary in Zanzibar’s historic capital Stone Town. This building was restored by the AKTC in the 1990s and has recently been converted by the AKHS into the Aga Khan Polyclinic. Professor Topan has jointly written a publication about the evolving story of this building.

Sir Tharia Topan encouraged Ismailis to emigrate from India and settle in Zanzibar and Mombasa. “These two were like springboards for Ismailis going on to the mainland. Some would come settle in Zanzibar or settle in Mombasa, but then they would also go inland into what is now mainland Tanzania and also mainland Kenya. So, there were these pioneers in Mombasa. You had Allidina Visram just after my grandfather's initial settlement. And then you had other pioneers as well, who we call nowadays ‘Ismaili pioneers’”.

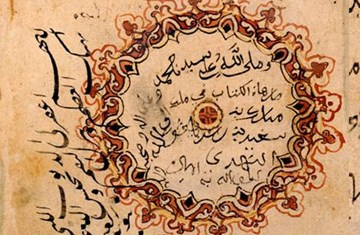

“Zanzibar was very cosmopolitan by the nature of its position geographically, so it had attracted people from various parts of not only Africa but also across the Indian Ocean and also along the East African coast... And of course, Zanzibar under the sultanate became a very important centre of Muslim learning. And then that really became quite a force in terms of knowledge and the scholars who came to Zanzibar to learn. And also, Zanzibar scholars went to Arabia, especially Yemen. They got their idafa (that is, their certificates) from there and then came back to Zanzibar to study.

“It's not just the Ismaili community, it is Zanzibar which was really quite advanced in its thinking. Because when you have a people who are cosmopolitan, who have good education, whose minds are so broad—I mean it's not that we didn't have narrow-minded people, of course we had. It was colonial education; the colonial education may be bad in one respect, but it was also good in other respects, because it introduces you to a larger picture, right from childhood.”

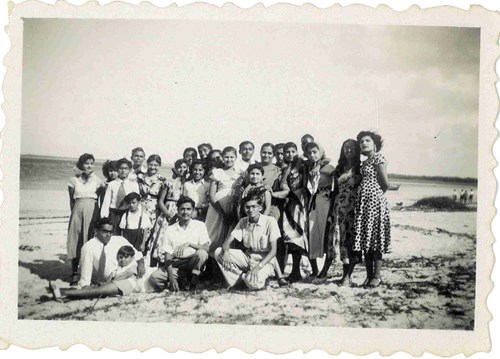

Zanzibar’s multiculturalism was not without its hurdles. Professor Topan goes on to explain how the relationship between the Ismaili community and others in Zanzibar changed over time. “I was the honorary secretary of the Young Muslim League, which was an association outside of the Ismaili Community…Up to 1955-56, the relationship between communities was excellent. There were, if you like, ethnic communities that had their own spaces: the Ismaili had their jamatkhana, the Ithna-’ashari mosque, the Bohra Mosque, all these masjids, the Hindu temples, the Parsis had theirs as well, each one of the Asian communities. And then the Europeans had their English clubs etc. There was this sort of ‘clockwork vision’, where you see all these cogs working in a clockwork, but the clock moves... And during Diwali, people would send greetings to one other, during Eid you send dishes one to another, so there was a lot of that.”

“Then came politics: a political awakening or consciousness. The Young Muslim League was totally educational; it had nothing to do with politics. But 1956 onwards, there was then another youth union which then became part of a political party and that sucked in all the other youths there, and then it changed.” The rise of political independence movements and ethnic nationalism carved a rift between these diverse communities in East Africa, culminating in 1964. But that’s another story altogether.

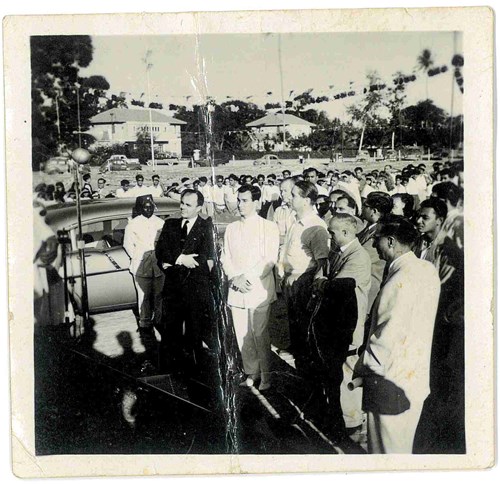

One of Professor Topan’s most cherished memories is having the honour of being selected at the age of just sixteen to recite the Qur’an during the Takht Nashini ceremony in 1957. This event marked the accession of His Highness the Aga Khan to his role as Ismaili Imam. Ismailis from all around East Africa travelled to Upanga, in Dar es Salaam, to see the new Imam take up his position. Professor Topan describes his experiences of the ceremony.

“Jaffaraly Dhala-Kassam, marhoum, came to me and told me he will go to Dar es Salaam for the [ceremony]. [He said] ‘These are the verses I want you to memorise, so I just followed these instructions, I memorised those verses…. I went to Dar es Salaam, and I didn't know anybody in Dar es Salaam, and of course it was a huge occasion with the Ismailis from all over Tanganyika and Zanzibar. Although they're going to have another ceremony in Nairobi, they came also [to Dar es Salaam] also because this was the first one.”

The next day, the 18th of October, Jafarally Dhala-Kassam and the young Farouk Topan travelled to Upanga. “From my point of view (I was 16) I thought that it was just people standing around. But actually, it was Hazar Imam [Aga Khan IV], Prince Aly [Salomone Khan], Sir Eboo [Pirbhai], Michael Curtis, [Vazir Abdullah] Tejpar, who was the president of the Council in Tanganyika, and Jafari Dhalla-Kassam. And [there were] missionaries: Abu Aly [Aziz], Sufi, Qadir Aly [Patel], and I do not know who the others are because I forget.”

Professor Topan describes how the stage was set up with two microphones. One by one, each missionary stepped up to a microphone and recited Surah al-Fatiha, the opening chapter of the Holy Qurʾan. “And then I went last,” recalls Professor Topan. “And then we were all told to wait. And then, there was a man called Mr Dosa and he said: ‘Hazar Imam wants to see you.’” The future Imam then put his hand on Farouk’s shoulder and told him: “’I would like you to recite tomorrow, but you need to do two things: one is get a copy of the Qurʾan and hold it, and the second thing is that [you should] come closer to the mic.’ This is advice I've been getting all throughout my life: talk closer to the mic, because my voice is soft.”

“There's a little funny story here because I went back to my dormitory, and they told me to be here by two o’clock,” Professor Topan explained, laughing. “But then they began to panic, because people were coming in from even before lunchtime and [asking] where is this boy? So, they started announcing: ‘Farouk Topan, could you come to the dais? Farouk Topan, could you come to the dais?’ And I was going to keep to my time. I didn’t even have a watch; I had borrowed a watch from a friend of mine. So, by the time I went there, the announcements had already been made, repeatedly.

“There was this Girl Guide on the carpet, a volunteer. I went to her and said: ‘Have they announced for Farouk Topan?’

She said: ‘Yes! Yes! Yes! Where is he?’

I said: ‘It’s me.’

She said: ‘It’s you?’ She couldn’t believe it. That was her immediate reaction: this young man with his pagri and his sherwani holding this book!” Professor Topan laughs at the memory. “And then, al-hamdu li’llah, things went alright.” Professor Topan described the Aga Khan approaching the takht and sitting in front of the crowd. When it was time for the Qurʾanic recitation, everyone stood up and the young Farouk recited Surah al-Fatiha perfectly.

“After the ceremony was over, the secretary of the federal council, Mr Dosa, came to me. He said: ‘Hazar Imam wants you to recite also in Nairobi and in Uganda, in Kampala.’” Farouk joined the entourage, reciting Qur’anic verses at other ceremonies across East Africa. “Nairobi was a challenge for me,” said Professor Topan as he recalls the sense of trepidation and nervousness he felt on this important occasion. “The stage was huge, in the sense that it was high… This meant that the first row had to be quite a way back, for people to see the stage. Because they knew I was going to recite, I was given a seat in the third row, on the aisle. Once Hazar Imam had walked on the carpet, ascended those steps and he had sat down, it was quite a while. And then I had to get up onto that carpet and walk—you can’t run, you have to walk in a very paced way—and then climb the dais to that microphone.”

Professor Topan’s eloquent recitation of the Qur’an would also be used later on other occasions of major significance to the Ismaili community - just one example of the many ways in which he has given service over the course of his lifetime.

In 1968, Professor Topan initiated the teaching of Swahili literature in the medium of Swahili itself, to the University of East Africa. “That was my real joy, to have all these young men and women around the table. There were about twelve or so of them, and that was wonderful.” Professor Topan also established the course in BA in Swahili and Linguistics a year later, just before the university split into three independent national universities in 1970. George Mhina, Muhammad Abdulaziz, and Professor Topan jointly wrote a paper at the vice chancellor’s suggestion, proposing the establishment of a department of Swahili. As a result, Professor Topan became the first head of the department of Swahili at Dar es Salaam in 1970. “We had a huge influx of students that year who wanted to do Swahili because the president of the country, Nyerere, had really been promoting Swahili as a unifying force against tribalism...quite a few of that cohort then became professors later on in their own right.”

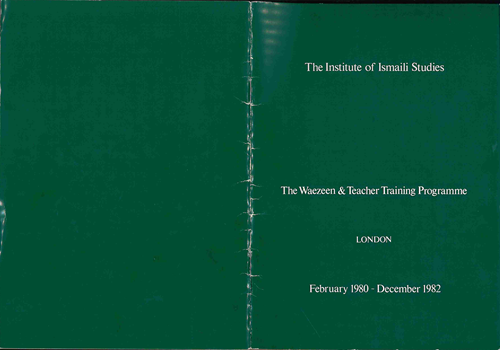

In 1971, Professor Topan returned to England to finish his degree, and then travelled to Riyadh to teach English and learn Arabic during the years 1975 to 1977. In October 1977, he was invited to join other prominent Ismaili scholars in the newly established Institute of Ismaili Studies in London. “That was the start of sixteen years with the IIS,” he says with his customary humility. The first IIS offices were at 52 High Holborn. “We had two rooms, and a big room which we then created into a library. By then, Dr Jalal Badakhchani joined us after the Iranian revolution of 1979. Mr [Amin] Haji joined and his wife, Zaibunissa, she was the librarian and [Mr Haji] taught Arabic to the first group.” The IIS then moved to Great James Street in the Bloomsbury area of London.

The first group of students started in February 1980 and finished in July 1983, after nearly three and a half years of study. “I can say this with my hand on my heart, it was a very, very thorough programme.” Professor Topan explains, “There were two ‘core’ programme parts which were all Ismailism, not that it was divorced from the bigger picture. You had wonderful lecturers that came to teach the first programme: Abbas Hamdani, Mohsin Mahdi, Alnoor Dhanani, we were all young in those days. You had Professor Madelung, Annemarie Schimmel, Daryoush Shayegan. We had a wonderful coterie. We were very fortunate to have a visit of the late Asaf Fyzee… And the first young PhD person was Böwering, Professor [Gerhard] Böwering, a German scholar who is now in the United States.”

Professor Topan shared the first IIS prospectus, outlining the course offerings. “I think that was the very first publication of the Institute—because what else would you call it?” he says, chuckling. Professor Topan then reflected on comments the early IIS had received on their pre-school series: “Those were the foundation of the whole Ta’lim series, because Hazar Imam gave guidance on the principles of that. Later on, it became then the topics, but it was very, very important.”

Professor Topan describes the three main parts of the early IIS course programme: Arabic-language immersion in Jordan, the core curriculum described earlier, and education. “Those prongs have, in a sense, continued into GPISH…. I was involved in the very first GPISH with [Dr] Farouk Mitha, Dr [Farhad] Daftary, and [Dr] Aziz Esmail. Then I left the year GPISH started, 1993, but we had prepared the curriculum up to that point.”

Since then, hundreds of students from dozens of countries around the world have attended courses at the IIS. It is just as much of a melting pot as the Zanzibar of Professor Topan’s youth. The Graduate Programme in Islamic Studies and Humanities and the International Training Programme for Wa’ezeen both continue the course of study that Professor Topan started in the 1970s: helping young Ismailis from around the world to become leaders in their communities.

Aside from being one of the founders of the IIS, and one of the first to establish Swahili Studies in Tanzania, Professor Topan has enjoyed an illustrious academic career. In 2022 he was awarded the status of professor emeritus in the Aga Khan University and an honorary fellowship at SOAS. Professor Topan is now retired but still plans to continue his scholarly and literary work with his seemingly boundless energy. “And now at last, having retired, I’m going to be doing the reverse of many academics, I’m going to publish my thesis…perhaps another book on Swahili culture, and then continue with my fiction, and then also something on Ismaili Tariqah, or perhaps some reflections on my life.”

The Oral History Project, at the Ismaili Special Collections Unit of The Institute of Ismaili Studies, seeks to preserve the memories, experiences, and stories of members of Ismaili communities across the world in their own voices.

Do you have a story to share with the IIS Oral History Project? If you want to share your memories, the story of your family, or the story of an elder you know, please reach out to the Oral History Project Coordinator, Rizwan Karim at rkarim@iis.ac.uk.