Bringing the World of Wladimir Ivanow to Life for AKC Gallery Exhibition

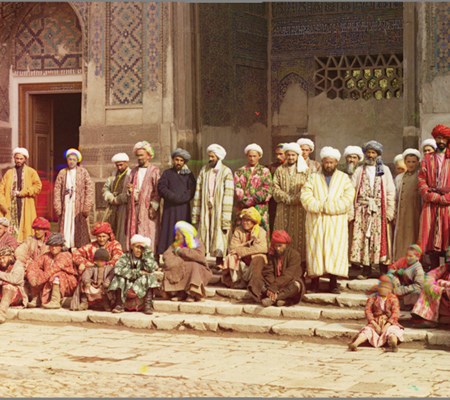

Men posing on the steps of the Registan, c. 1915, by Prokudin-Groskii. Image credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington DC.

"Wladimir Ivanow and Modern Ismaili Studies” is currently running at the Aga Khan Centre Gallery. In this personal piece, Russell Harris, who helped to plan the exhibition, reflects on the challenges and joys of bringing the scholar (1886-1970) and his work back to life.

Planning an exhibition of images related to a book is tantamount to preparing a truncated version of a Shakespeare play in a West End theatre. Every book is rich in nuance. A book dealing with historical events and intellectual history has the difficult task of applying emphasis, or even mentioning a select group of facts, in order to form a narrative. Where this narrative takes us and how gripped we are by it depend upon the skill of the author. Fortunately, when this task falls into the hands of Dr Farhad Daftary, Co-Director of the IIS and the editor of Fifty Years in the East: The Memoirs of Wladimir Ivanow, the reader is gifted with a text that provides an expert narrative based on extensively researched references, great historical insight, appreciation and respect for the subject’s life-long endeavours and a use of English that is both academic and clear.

Although I was brought into this project at a relatively early stage in this book’s process, this was to create potted biographies of the numerous orientalists named by Ivanow. Stage two was the request to find illustrations for the printed book—but here I wish to speak briefly of the process of creating an exhibition on the life and work of Ivanow with very little material to go on. Firstly, the whereabouts of any existing personal effects of Ivanow are known to no one—hence there are neither photograph albums for a curator to plunder nor possessions around which to build a story. What we are left with is the printed output of Ivanow, a small number of photographs of Alamut and the regions on which he published, one carte-de-visite style photographic portrait of him as a young man from a fashionable studio in Tsarkoe Selo, Russia, and two casual ”snaps” where a young Ivanow appears to be relaxing somewhere in India. All in all, very little.

In finding images for an exhibition, one must always look for those with a high degree of relevance to the subject, particularly as this is a documentary exhibition. The ramifications of this are that in looking for illustrative visual material we are limited to the sites mentioned by Ivanow and his time, with a generous allowance for material a few years either side. The exhibition is not a reflection of my preferences for showing remarkable images, or throwing side-lights on great historical photographs such as the amazing colour images made by Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii (1863-1944), but fortunately I managed to find two images and am going to rhapsodise over one of them in the next sentence! The beauty of this very early colour photograph of “Men posing on the steps of the Registan, Samarkand” (pictured above) overturns all our preconceptions of the dusty, sepia-toned hues of much of the usual imagery of Central Asian scenes. Prokudin-Gorskii’s images required some patience, as the camera had to take three shots using different colour filters, and we can see in the bottom right that some of the seated younger boys fidgeted, resulting in slightly blurred faces—whereas the adults all seem to have been able to stand stock-still!

To collate material for the exhibition, I researched works cited by Ivanow, those cited by Dr Daftary, my own digital collection of images of Central Asia, Russian archives and the Library of Congress digital archives, among others. Collecting images for an exhibition, one has to throw a wide net and carefully sift the results. And the great enjoyment of a project like this is having the time, and reason, to look through acres of photographs of Tehran, Bombay, Cairo and Damascus, to trawl through travelogues in the hope that they might contain illustrations, and to consider that watercolourists or architectural artists might have captured the right moments in time. Most of the small portraits of the eminent orientalists seen in the exhibition have been provided by the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, Russian Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg.

Having assembled a mass of visual material, there then begins a process of whittling down until we are left with an illustrated narrative that neither disrespects the subject, nor the viewer for their time. During the week-long process of installing the exhibition, which was designed by Esen Kaya, the Aga Khan Centre’s brilliantly talented curator, I offered a sneak peak to a few of the exhibition’s stakeholders. This was essentially an act of market research, as the lead curators Esen Kaya, Dr Taushif Kara and I wanted to benefit from the acute vision of Dr Daftary, Dr Shainool Jiwa and Dr Daryoush Poor. We listened to their comments, discussed them and made a few final tweaks to the exhibition.

To those who have not yet visited the exhibition, please do. Ivanow’s pioneering work on uncovering the lost treasures of Ismaili history and intellectual heritage played a foundational role in the establishment of The Institute of Ismaili Studies. The images on display, as well as the coins and manuscripts from the Ismaili Special Collections Unit, and the printed works kindly loaned by Dr Daftary, all bring to life Wladimir Ivanow and his work. We find ourselves walking in his footsteps throughout his life-long endeavour of uncovering the history of the Ismaili community and its rich intellectual heritage.

Russell Harris