The Ismailis and their Role in the History of Medieval Syria and the Near East

Abstract

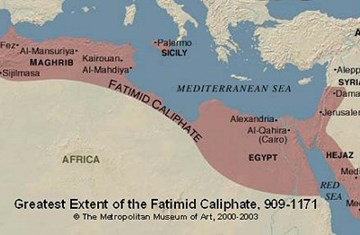

Whether overtly or covertly, the Ismailis have played an important role in the cultural history of Islam, particularly in Syria and Egypt, where they constituted the Fatimid , which was to last for around 200 years. After the fall of the in 1171 CE and during the subsequent diaspora, they became famous for their strongholds in Iran and Syria, from where they intervened in the various conflicts between Christian powers and the Muslim kingdoms in the Holy Land.

In religious terms, the Ismaili community is part of the larger diversity of the worldwide Muslim Over the passage of time, Muslims constituted a variety of groups, which exemplified diverse ways of understanding the primal message of Islam and different approaches to how that commonly held message could be reflected in the practical life and organisation of the community. The Ismailis are one such group. They are part of the branch of Islam, the Sunni being the other major branch, and have always constituted a minority, historically and in the contemporary world. At present, the Ismailis live in over twenty-five countries, in virtually every region of the world. In some of these regions, their history goes back over a thousand years. Syria is one such example where the Ismaili presence can be dated to the 9th century.

Among the Shi'a, there were those who remained faithful to the line of Imams who descended from Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq (d. 765 CE) through his son, Imam Ismail. Hence, they came to be known as Ismailis. There were other Shi'i groups who gave their allegiance to different lines of Imams. The largest group among such other Shi'is are called Ithna'ashari; they believe in a line of twelve Imams, ending in the who remains in occultation (ghayba) and would reappear to grant salvation at the end of time.

Introduction

Whether overtly or covertly, the Ismailis have played an important role in the cultural history of Islam, particularly in Syria and Egypt, where they constituted the Fatimid caliphate, which was to last for around 200 years. After the fall of the Fatimids in 1171 CE and during the subsequent diaspora, they became famous for their strongholds in Iran and Syria, from where they intervened in the various conflicts between Christian powers and the Muslim kingdoms in the Holy Land.

In religious terms, the Ismaili community is part of the larger diversity of the worldwide Muslim umma. Over the passage of time, Muslims constituted a variety of groups, which exemplified diverse ways of understanding the primal message of Islam and different approaches to how that commonly held message could be reflected in the practical life and organisation of the community. The Ismailis are one such group. They are part of the Shi‘a branch of Islam, the Sunni being the other major branch, and have always constituted a minority, historically and in the contemporary world. At present, the Ismailis live in over twenty-five countries, in virtually every region of the world. In some of these regions, their history goes back over a thousand years. Syria is one such example where the Ismaili presence can be dated to the 9th century.

Among the Shi‘a, there were those who remained faithful to the line of Imams who descended from Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq (d. 765 CE) through his son, Imam Ismail. Hence, they came to be known as Isma‘ilis. There were other Shi‘i groups who gave their allegiance to different lines of Imams. The largest group among such other Shi‘is are called Ithna‘ashari; they believe in a line of twelve Imams, ending in the Mahdi who remains in occultation (ghayba) and would reappear to grant salvation at the end of time.

A Wide-Spread Network with Shifting Power Bases

The difficult and divisive political climate of the time caused the early Ismaili Imams, fearing persecution, to maintain anonymity. According to Ismaili historical sources, they lived during this time in Salamiyya in central Syria. It was from Salamiyya that the Imams secretly guided the activities of their followers from North Africa to Khurasan and Central Asia. During this early period, dating to the middle of the 9th century, the community came to be organised through the institution known as the da‘wa. Although the term was not confined to the Ismailis, their skilful organisation and effective communications gave it a very unique character at the time. The individuals representing the da‘wa were known to lead exemplary ethical lives and possessed a keen knowledge of the highest intellectual sciences of the day. Known as da‘is, they also combined knowledge of diplomacy and public relations. Their role was to summon people to the cause of Islam and of the Ismaili Imams and to promote the social, moral and spiritual welfare of the community and the regions in which they lived.

The combined efforts of members of the da‘wa created strong support for the Imams in North Africa, Yemen and Syria. It was however from Syria that the Imams guided the activities of their followers in these different regions. Even after the Ismaili Imams began to rule as Fatimid caliphs in Cairo, Syria continued to be an important region for their da‘wa activities, also comprising one of the dominions of the Fatimid state. Syrian Ismailis have therefore constituted an important part of the Ismaili community throughout its history.

The history of Egypt itself, where the Fatimid rulers were in power from 969 CE to 1171 CE, experienced a long period of prosperity, during that period. The Fatimids established strategic control over Mediterranean and Red Sea trade routes with Cairo serving as an entrepôt. They generated a flourishing era of commercial activity which included Syria. Under Fatimid rule, Egypt participated vigorously in international trade with lands such as India and the Far East,

North Africa, Nubia, Europe, Byzantium (Constantinople in particular), Sicily and other islands of the Mediterranean. Agriculture led to self-sufficiency, and industry was promoted. Various religious communities, Jewish, Christian and Muslim, lived together in a spirit of mutual respect and enjoyed prosperity under the relative stability of the time.

It was, however, in the sphere of intellectual life that Fatimid achievements seem most brilliant and outstanding. The Fatimid rulers were lavish patrons of learning, and their generous encouragement of scientific research and cultural activity caused Cairo, their newly founded capital, to exert a degree of magnetic attraction, such as to draw renowned mathematicians, physicians and astronomers to the city from all over the Muslim world. Within the royal court, noted poets such as Ibn Hani and Tamim b. al-Mu‘izz, and historians and geographers such as al-Musabbihi and al-Muhallabi, flourished under the patronage of the Fatimids. The universities of al-Azhar and Dar al-‘Ilm provided a monumental and enduring testimony to the Fatimids’ love of learning. Figures of outstanding ability, such as Abu Ya‘qub al-Sijistani, Qadi al-Nu‘man, Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani, al-Mu‘ayyad fi’l-Din al Shirazi and Nasir-i Khusraw, made crucial contributions to the articulation of Ismaili thought which was characterised by a remarkably complex upsurge of intellectual activity which M. Canard in the Encyclopaedia of Islam has described as analogous to that which took place in Europe in the 18th century. The cultural impact of the Fatimid state was not confined to the Muslim world. At the height of its power, while the Fatimid fleet and commerce dominated the eastern Mediterranean, the influence of the universities in Cairo spread into Europe, with Fatimid writers contributing significantly to the development in the West of sciences such as optics, medicine and astronomy.

When the Persian poet and thinker Nasir-i Khusraw visited Cairo in 1047 CE, he was amazed by the high level of prosperity and the security enjoyed by its citizens. “I saw such personal wealth there,” he records in his Safarnama (Book of Travels),1 “that were I to describe it, the people of Persia would never believe it.” He goes on to report that “the security and welfare of the people have reached a point that drapers, money changers and jewellers do not even lock their shops - they just lower a net across the front, and no one tampers with anything.”

The Fatimids attached great value and importance to education and learning. They established one of the world’s earliest universities. Founded in 970 CE as the mosque of al Azhar (meaning ‘House of Illumination’), it was later transformed into a university with its own curriculum, lecture halls and residences for teachers and students, funded generously by the Imams. Al-Azhar became the foremost Fatimid institution of higher learning, specialising in various religious sciences such as Qur’anic studies, theology and law.

Another important academic institution of the Fatimids was the Dar al-‘Ilm (‘House of Knowledge’), also known as Dar al-Hikmah (‘House of Wisdom’). Founded by the Fatimid Caliph-Imam al-Hakim in 1005 CE, this academy was accommodated with its own library in a section of the Fatimid palace. It is likely that Hasan-i Sabbah himself, the future founder of the Ismaili State in Iran, received some of his advanced education at this academy when he visited Cairo in 1078 CE.

It was during the Alamut period in Nizari Ismaili history that Syrian Ismailis acquired major prominence and became well-known in Europe. In the final decades of the 11th century a group of Ismailis under the leadership of Hasan-i Sabbah (d. 1124 CE) established a state in Iran. They had given allegiance to Imam Nizar, the eldest son and designated as Imam by the last effective Fatimid Caliph-Imam al-Mustansir billah, who died in 1094 CE. As part of a policy of consolidating relationships with other Ismailis, Hasan-i Sabbah sent emissaries to Syria to assist the community in its organisation. Syria was politically fragmented. The first Turkoman bands had entered Syria as early as 1055 CE, and the country was subsequently invaded by the Saljuq armies. By 1078 CE, the whole of Syria, apart from a coastal strip retained by the Fatimids, was under Saljuq rule or suzerainty; Tutush, the brother of the Great Saljuq Sultan Malikshah, had come to be recognised as the Saljuq overlord of Syria. As in Persia, Saljuq rule in Syria had caused many problems and was resented by the Syrians who were divided amongst themselves and unable to expel the invaders. In time, factional fights among the Saljuqs caused widespread disruption and Syria was broken into a number of smaller states. It became the scene of rivalry among different Saljuq princes and amirs, each one claiming a part of the country, while various minor local dynasties were at the same time attempting to assert their independence.

The political fragmentation of Syria became more pronounced by the appearance of the Crusaders in 1097 CE. Starting from Antioch, the Crusaders advanced swiftly along the Syrian coast and settled down in the conquered territories, establishing four Latin states based in Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli and Jerusalem. The Frankish encroachment of Syria naturally added to the apprehensions of the local population, complicating the Saljuq quarrels. In these troubled times, the most important Saljuq rulers of Syria were Tutush’s sons Ridwan (1095 CE-1113 CE) and Duqaq (1095 CE-1104 CE), who ruled respectively from Aleppo and Damascus.

The Ismailis therefore had to develop a strategy for survival and sustainability in these troubled regions. An evident solution to this problem was to create well-fortified centres where the community would find protection and freedom to organise and practise their faith. Over time, they were successful in obtaining a number of fortresses in the mountain area known then as the Jabal Bahra, today called the Jabal Ansariyya after its Nusayri population.

The Ismailis in Medieval Syria

The first Nizari leader in Syria, mentioned by the Damascene historian Ibn al-Qalanisi and later sources, was known as al-Hakim al-Munajjim, the physician astrologer. Probably accompanied by a number of supporters from Alamut, he appeared in Aleppo, and, by the very beginning of the 12th century CE, managed to find a protector in the city’s Saljuq ruler, Ridwan. Aleppo, in northern Syria, proved to be a hospitable environment. It had an important Shi‘i population and an existing link with Ismailis. They were thus able, under the protection of the ruler, to establish themselves in Aleppo from where they could build linkages with other Ismaili communities.

In due course, the Ismailis tried to extend their influence, with the support of the ruler of Aleppo, to adjoining areas and soon came in conflict with the invading Crusaders who had designs of their own for acquiring certain fortifications in the region. In the ensuing conflict, several Ismaili leaders and others were killed. This was probably the first encounter between the Nizaris and the Crusaders in Syria. In 1110 CE, the Ismailis also lost Kafarlatha to the Crusaders, a lesser locality in the Jabal al-Summaq, which had come into their possession sometime earlier.

Following the death of Ridwan in 1113 CE, the Ismaili fortunes began to be reversed in Aleppo, since Ridwan’s young son and successor Alp Arslan adopted a more hostile stance towards them. Many Ismailis were killed in ensuing conflicts. Some two hundred Ismailis of Aleppo were also massacred or imprisoned and their properties were confiscated. Many, however, managed to escape to different areas, some even finding refuge in Frankish territory. While unsuccessful in retaining a base in this region, many positive contacts had been made with the local population who was generally supportive and sympathetic to the Ismaili presence.

During the second period of their initial efforts to establish themselves, the Syrian Ismailis concentrated their activities in southern Syria. In 1124 CE the new ruler of Aleppo, arrested the local leader of the Ismailis and ordered the expulsion of the Ismailis who sold their properties and departed from the city. The Ismaili centre of activities now shifted to Damascus and other localities nearby. There, the Ismailis supported the local communities against threats from the Crusaders, joining them in defending the major centres. The Turkish atabeg (regent) of Damascus received Bahram, the Ismaili leader, with honour and gave him official protection, further enhancing the position of the community there. At the same time, Bahram found an influential and reliable ally in the ruler’s vizier, Abu Ali Tahir b. Sad al Mazdaqani. Bahram requested that the community be given a fortress from which to defend themselves, and in 1126 CE Tughtigin, the ruler, ceded the fortress of Baniyas, on the border with the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, which was then menaced by a Crusader army. Enjoying the continued support of al-Mazdaqani, Bahram was also given a building in Damascus which he used as local headquarters. Henceforth, Bahram further fortified Baniyas, developing residential facilities for himself and other Ismailis.

In 1129 CE, the governor of Damascus turned on the community against the Ismailis and a massacre followed. His militia destroyed Ismaili homes and fortifications; those who survived the onslaught were forced to flee. The fortress in Baniyas was surrendered to the Franks, who were simultaneously advancing on Damascus. This ended a turbulent period in the attempts of the Ismailis of Syria to find a base for themselves in a very divided region beset by internal rivalries and external threats.

The surviving Ismailis concentrated their efforts on acquiring a network of safe strongholds. They directed their attention to the Jabal al-Bahra, a mountainous region between Hama and the coastline southwest of the Jabal al-Summaq, which was inhabited by Nusayris and possessed a number of suitable castles. Few details are known about the Syrian Nizaris and their da‘is during this period, when they transferred their activities out of the cities, but it seems that they were able to recover swiftly from their setback in Damascus.

After reorganising under the leadership of Abu’l-Fath, they established themselves in the Jabal Bahra, where the Crusaders had failed to gain permanent strongholds. In 1132-33 CE, the Nizaris came into possession of their first fortress in the Jabal Bahra by purchasing Qadmus from the local warlord of Kahf, Sayf al-Mulk b. ‘Amrun who, with the assistance of the Nusayris, had recovered the place from the Franks the previous year. From Qadmus, which became one of their major centres and often served as the residence of their leader, the Syrian Ismailis extended their presence in the region. Shortly afterwards, they acquired Kahf and were also able to drive out the Frankish occupants of the fortress of Khariba.

In 1140-41 CE, the Nizaris were able to control Masyaf, their most important stronghold in Syria. Masyaf, situated about forty kilometres to the west of Hama, subsequently served as headquarters of the Ismaili leadership in Syria. They also captured several other fortresses in the Jabal Bahra, including Khawabi, Rusafa, Maniqa and Qulay’a, which became collectively designated as the qila‘ al-da‘wa or the fortresses of the da‘wa. The famous Crusader chronicler William of Tyre, writing a few decades later, puts the number of these castles at ten and the Ismaili population of the region at 60,000.

The Ismaili Strongholds in Syria and Iran

Indeed, in less than twenty years after their misfortunes in Damascus, the Syrian Ismailis had succeeded in establishing a network of mountain fortresses and consolidating their position despite the hostility of the local rulers and the threats posed by the Crusaders, who were active in the adjacent areas belonging to the Latin states of Antioch and Tripoli. As in Iran, however, they remained a local power controlling a particular territory and enjoying for some time an independent status.

Life inside the castle would have been spartan and uncomfortable at the best of times. In winter the temperatures are always icy, with freezing gales blowing down from the snowy peaks surrounding the valley. In spite of the altitude, the summer months are hot and dusty, requiring the greatest vigilance for attacking forces. The castle itself would have been the centre of continuous activity in all seasons. The water channels and cisterns had to be kept clean, the armourers were busy forging new weapons, the carpenters and masons constructing or maintaining mangonels, or repairing and enlarging the defences. The cooks were busy in the kitchens, replenishing the food stores and keeping them in good order. Study, learning and discussion filled the day for many, especially for those who aspired to become da‘is.

Our account of life in the castles of Iran and Syria is based on historical data and archaeological evidence. The same pattern is likely to have been replicated in all the great fortresses of the Ismailis, such as Maymundiz, Girdkuh and Qain in Iran and Masyaf and other Syrian castles, too. Time was spent in general maintenance and defensive work. Much of the mythology surrounding the castles and the Ismailis is based largely on the highly unreliable account of the Venetian traveller Marco Polo, which became accepted by many as fact until disproved by modern scholarship.

Marco Polo recounts during his journey to the court of the Mongol ruler Kublai Khan in the years 1271-1290 CE that while passing through northeast Iran, he heard from local people about the ‘Old Man of the Mountain’ and his fanatical band of devotees who lived in a remote valley hidden in the mountains. The ‘Old Man’ was said to have built a garden in which there was a palace where young men were seduced by drugs and wine into believing that they were in Paradise as a reward for their acts of assassination.

The fictional nature of Marco Polo’s account was long suspected by scholars, and its absurdities have been exposed more recently by various scholarly accounts. The very name ‘Old Man of the Mountain’ was never used in the Persian sources for Hasan-i Sabbah, but applied in fact to Rashid al-Din Sinan of Syria. The persistent legend that the Ismaili fida’is were drugged and received a foretaste of Paradise before being sent out on their mission is clearly as absurd as it is fantastical. There is no contemporary Muslim evidence that this was so.

We know further that when the historian Juwayni inspected Alamut after its surrender to the Mongols in 1256 CE, he was greatly impressed by its library, water-cisterns and storage facilities, but he makes no mention of any delectable secret garden or sumptuous palace inside or outside the castle. It is unfortunate that Juwayni himself, after having examined the original Ismaili documents and finding them full of “heresy and error” cast them into the flames. The distortion of Ismaili history was thus often based on sheer invention and fabrication.

The leadership of the Ismailis in Syria now came to be assumed by their most famous leader Rashid al-Din Sinan. One of the prominent figures in Ismaili history, Sinan b. Salman (or Sulayman) b. Muhammad Abu’l-Hasan al-Basri, known also as Rashid al-Din, was born into a Shi‘i family in ‘Aqr al-Sudan, a village near Basra on the road to Wasit. Sinan was brought up in Basra, where he became a schoolmaster and adopted Ismailism. Subsequently he went to Alamut and studied under the future Imam, Hasan II. During his stay at Alamut, Sinan studied philosophy and in particular the well-known works of the Fatimid and Nizari periods as well as benefiting from the library and other intellectual resources in Alamut. Soon after his accession to power in 1162 CE, Imam Hasan II sent Sinan to Syria. Initially, Sinan remained at Kahf, one of the major Nizari fortresses in the Jabal Bahra, making himself extremely popular with the local Nizaris, until Shaykh Abu Muhammad, the head of the Syrian Nizari da‘wa died in the mountains. Soon afterwards, Sinan assumed the leadership of the Syrian da‘wa on the instructions of the Imam.

Once established, Sinan began to consolidate the position of his community while building relations with neighbouring rulers as well as the Crusaders who constituted, by their presence, a general threat to all. He rebuilt the fortresses of Rusafa and Khawabi, fortified and constructed other strongholds, and captured the fortress of Ullayqa, near the Frankish castle of Marqab held by the Hospitallers. At the same time, while moving among the various Nizari castles, especially Masyaf, Kahf and Qadmus, Sinan rapidly reorganised the Nizari community.

Externally, Sinan aimed to protect the Ismailis from various potential threats and to balance the various interests in the region. Clearly the Ayyubids under Salah al-Din represented a stronger threat than the Crusaders at this time. Recognising existent realities, Sinan adopted suitable policies in his dealings with the outside world; policies which were revised when needed to reassure the safety and independence of his community. As a result, from early on, Sinan established peaceful relations with the Crusaders, who had been sporadically fighting the Nizaris for several decades over the possession of various strongholds.

Meanwhile, the Nizaris had acquired a new Frankish enemy in the Hospitallers, who in 1142 CE had received from the lord of Tripoli the celebrated fortress of Crac des Chevaliers (Hisn al-Akrad) at the southern end of the Jabal Bahra. The Nizaris continued to have minor entanglements with the Hospitaller and Templar military orders, which owed their allegiance directly to the Pope and often acted independently. Subsequently, around 1173 CE, Sinan sent an embassy to King Amalric I, seeking a formal rapprochement with the kingdom of Jerusalem. The negotiations were evidently proceeding successfully. But the Templars disapproved of this Nizari embassy, and on their return journey Sinan’s emissaries were ambushed and killed by a Templar knight. Amalric took punitive measures against the Templars, but as he himself died soon afterwards in 1174 CE, the negotiations between Sinan, known to the Crusaders as the ‘Old Man of the Mountain’, and the Franks of Jerusalem proved fruitless.

When Sinan assumed power, Nur al-Din, the Zengid ruler of Syria, was preoccupied with his policies against the Crusaders and the later Fatimid caliphs who were recognised as Imams only by the Musta‘li Ismailis. Nevertheless, relations between Sinan and Nur al-Din remained relatively tense, due to the activities of the Ismailis in northern Syria. But Nur al-Din, who finally succeeded through Salah al-Din in overthrowing the Fatimids in 1171 AH, did not attack the Ismailis, though it is reported that he was planning a major expedition against them just before his death. The death of Nur al-Din in 1174 CE, the same year in which Amalric I died, finally gave Salah al-Din his opportunity to act as the champion of the Muslims and the leader of the holy war against the Crusaders. As the strongest of the Muslim rulers in the area, Salah al-Din strove towards incorporating Egypt, Syria and Iraq into his nascent Ayyubid empire. As a result, he targeted the Ismailis of Syria, as well as the rulers of Aleppo and Mawasil. Salah al-Din entered Damascus in 1174 CE and in the following year invaded the Ismaili territory besieging Masyaf. The siege was brief and following mediation by a local governor, Salah al-Din concluded a truce with Sinan and withdrew his forces from the area. Henceforth, hostilities ceased between the two men, who had come to an agreement on peaceful co-existence.

Rashid al-Din Sinan died in 1193 CE in the castle of Kahf. In the course of some thirty years, Sinan had led the Syrian Nizaris to a position of power and influence. The ablest of their chiefs, he gave the Syrian Nizaris an independent identity; with their own sphere of influence, a network of strongholds and a strong organisation. His shrewd strategies and appropriate alliances with the Zangids, the Crusaders, and Salah al-Din, served to ensure the independence of the Ismailis of Syria in difficult times.

The inscriptions at Masyaf, Kahf and other strongholds, and from a few Syrian literary sources indicate continuity after Sinan’s death. The Ismailis were led by several able individuals until 1258 CE, in consultation with the Imams in Alamut. Like the Nizari community in Quhistan, in eastern Persia, the Syrian Nizaris continued during this period to exercise a certain degree of local initiative in dealings with their Muslim and Frankish neighbours. The Syrian Ismailis had, on the whole, maintained peaceful relations with Salah al-Din’s Ayyubid successors in Syria. But occasional conflict continued in their dealings with the Franks, who still held the Syrian coast.

There were over 60 castles and forts in the Alamut valley and in Rudbar, about 80 in Khurasan, and some 50 in other parts of Iran. In Syria, the Ismailis held 60 castles of various sizes in the Jabal Bahra between Aleppo and Damascus. Thus in Iran and Syria there were some 250 fortifications, illustrating the extent and organisation of the Ismailis. All the major fortresses were well-built and provided for, with cisterns of water fed by springs or rain water and well-supplied with provisions, stored in huge underground chambers. Their libraries, too, were renowned and the objects of much envy.

“There can be no doubt”, says Peter Willey, “about the efficiency of the Ismaili administration. This is reflected most impressively in the immense logistical tasks involved in the construction and maintenance of more then 200 castles scattered over vast distances. The construction of new castles required, first of all, detailed survey work and planning of a high order. The execution of the project must have been carried out by a group of supervisors in charge of quarrying the required stonework, and its transportation to the castle site. Under their command would be teams of masons, builders, water engineers, plasterers and other skilled workers. The huge amounts of stone required for keeping the castles and garrisons in good repair for many months and even years demanded what we would call today a quartermaster general and his staff of the highest quality. Finally, the continuous construction and strengthening of these castles would not have been possible without a large and permanent labour force, moving from one site to another as required. We have no information on the composition of these workers, although a good portion of them are certain to have been Ismailis recruited and trained locally.” 2

Between Crusaders and Mongol Invasions

In the previous section, reference has already been made to the relations between Sinan and the Crusader kingdoms in the Holy Land. Other historic contacts need to be mentioned here. In 1227 CE, Frederick II (1212-1250 CE), the Emperor of Germany who went to the Holy Land on his own Crusade, sent envoys to Majd al-Din, the Syrian Ismaili leader. However, around the same time, the Hospitallers who had been highly displeased with the dealings between the Ismailis and Frederick II, demanded a tribute from the Ismailis. The Ismailis refused, announcing the fact that indeed they themselves were recipients of gifts and payments from Frankish emperors and kings.

The last important event in the history of the Ismaili community of this medieval period relates to the dealings between them and Louis IX, better known as St Louis, the French king who led the Seventh Crusade. These dealings, recorded by Jean de Joinville, the king’s biographer and secretary, occurred soon after the arrival of St Louis in ‘Akka (Acre) in May 1250 AH. At the time, they were most probably still under the leadership of Taj al-Din Abul Futuh, whose name is mentioned in an inscription at Masyaf dated February-March 1249 CE. At any rate, Ismaili emissaries came to the French king and asked him either to pay tribute or at least release them from the tribute which they themselves paid to the Templars and the Hospitallers. On the intervention of Reginald of Vichiers and William of Chateauneuf, the Grand Masters of the Temple and the Hospital, the negotiations between the Ismailis and St Louis did not lead to any results. St Louis, himself more interested in establishing friendly relations with the Mongols, did not pay any tribute to them. But the French king and the Syrian Ismaili leadership exchanged gifts. It was in the course of these embassies that the Arabic-speaking friar Yves le Breton met with Ismaili scholars and discussed religious doctrines in Masyaf.

The Mongol onslaught on the Muslim world and in particular on the Ismaili state in Iran must have disheartened the Syrian community, who could no longer count on the support and leadership of Alamut and the personal guidance of the Nizari Imam after the destruction of Alamut in 1256 CE. Considerably weakened, the Syrian Ismailis eventually submitted to al Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars I (1260-1277 CE), the Bahri Mamluk Sultan of Egypt, who soon extended his hegemony over Syria and its different principalities.

Meanwhile, having destroyed the Ismaili state of Iran, Hulagu, the Mongol conqueror had proceeded towards his second major objective, the extinction of the Abbasid caliphate. By February 1258 CE, the Mongols seized Baghdad and devastated the ancient capital of the

Abbasids for a whole week. The Caliph al-Mustasim, who had endeavoured in vain to prevent the Mongol cataclysm, was put to death on Hulagu’s orders. Hulagu’s third campaign was directed against the Ayyubid states in Syria. In 1260 CE, the Mongols seized Aleppo, and soon afterwards Hama and Damascus surrendered to the Mongols. In March 1260 CE, Ket-Buqa, who had been in charge of the advance operations of the Mongols in Syria, made his triumphal entry into Damascus. It was during the same year, 1260 CE, that four of the Nizari fortresses, including Masyaf, were surrendered to the Mongols by their governors. The Mongol success in Syria was, however, short-lived. Hulagu returned to Iran in the summer upon hearing the news of the Great Khan Mongke’s death, which in fact had occurred a year earlier in 1259 CE, leaving Ket-Buqa in command of his reduced forces in Syria. In 1260 CE, the Mongols suffered a drastic defeat at Ayn Jalut, in Palestine, at the hands of the Mamluk armies of Egypt, led by Sultan al-Muzaffar Qutuz (1259-1260 CE).

The vanguard of the Mamluk forces was commanded by Baybars, who succeeded Qutuz to the Mamluk sultanate and thwarted the Mongols in their subsequent attempts to establish themselves in the region. Soon, the Mongols were expelled from all of Syria, where Baybars rapidly emerged as the dominant power. The Ismailis were now faced with the challenge of developing relations with the Mamluks and other Muslim rulers whom they joined in repelling the Mongols from Syria. They also recovered the four fortresses which they had earlier lost.

Epilogue: The Ismaili Community under the Mamluks

The Ismailis attempted to consolidate their relations with Baybars by sending him embassies and gifts. Baybars, who was then preoccupied with the Mongols and the Franks, reciprocated by granting certain favours to the community. Nonetheless, from early on Baybars systematically adopted measures which ultimately led to the loss of the independence of the Ismaili community. They eventually granted rights to Ismaili territories to al-Malik al-Mansur (1244-1285 CE), the Ayyubid prince of Hama. The Ismailis however retained possession of eight permanent strongholds, Masyaf, Qadmus, Kahf, Khawabi, Rusafa, Maniqa (Maynaqa), Ullayqa and Qulay’a.

Increasingly, Baybars compelled the Ismailis to adhere to a practice of paying them tributes and ensuring that they acknowledged the suzerainty of the Mamluk state. Around 1270 CE, Baybars demanded possession of Masyaf, which was to be entrusted to one of his own amirs, Izz al-Din al-Adimi. Sarim al-Din, who was to hold the Nizari castles as the deputy of Baybars, proceeded to take charge of them. But Sarim al-Din, too, angered the sultan by attempting through trickery to take possession of Masyaf, in violation of the sultan’s instructions. Once inside, he put to death a large number of the residents of Masyaf, who, abiding by the sultan’s orders, had refused to yield the castle to him. On Baybars’ request, al Malik al-Mansur, the ruler of Hama, dislodged the rebellious Sarim al-Din from Masyaf and sent him as a prisoner to Cairo, where he later died.

By February 1271 CE, Baybars had decided to deal more assertively with the Ismailis. Their leaders were arrested and forced to surrender control of the fortresses to the Mamluks. The Ismaili castles now began to submit in rapid succession to Baybars, who used military blockades, threats and negotiations in dealing with the Ismailis. Ullayqa and Rusafa surrendered in May 1271 CE, and by May 1273, Khawabi, Qulay’a, Maniqa and Qadmus had also capitulated. The residents of Kahf mustered some resistance, and with the fall of that fortress in July 1273 CE the last independent Nizari outpost in Syria fell into the hands of the Mamluks, less than three years after Girdkuh, the last stronghold in Iran had surrendered to the Mongols.

The Ismailis were permitted to remain in their fortresses in the Jabal Bahra, but only under the strict supervision of Mamluk lieutenants. Amongst the later medieval sources speaking of the Syrian Nizaris, an elaborate account is related by the celebrated Moorish traveller lbn Battuta, who passed through Syria for the first time in his travels in 1326 CE. He names Maniqa, Ullayqa, Qadmus, Kahf and Masyaf as the fortresses which were still in the hands of the Ismailis, and then proceeds to give interesting details on the arrangements existing between them and the Mamluk Sultan al-Nasir Nasir al-Din Muhammad, who reigned intermittently between 1294 CE and 1340 CE. The Syrian Ismailis thus lived at the time as loyal subjects of the Mamluks and after them, the Ottoman Empire’s representatives in Syria.

In the midst of fluctuating political fortunes, the Ismailis of Syria as elsewhere, sought to maintain, as far as was possible, an active and vibrant intellectual and cultural life. As the late Marshall Hodgson observed: “The Ismaili society was not a typical mountaineer and small town society (...) Each community maintained its own sense of initiative in the framework of the wider cause, and probably a sense of large strategy was never completely absent (...) but what was most distinctive was the high level of intellectual life. The prominent early Ismailis were commonly known as scholars, often as astronomers, and at least some later Ismailis continued the tradition. In Alamut, in Kuhistan, and in Syria, at the main centres at least, were libraries (...) which were well known among Sunni scholars. To the end the Ismailis prized sophisticated interpretations of their own doctrines, and were also interested in every kind of knowledge which the age could offer.”3

- Nasir-i Khusraw, Safar-name [“Books of Travels”], N.W. Pur, Tehran 1972

- P.Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, London 2005

- M.G.S. Hodgson, The Order of Assassins, The Hague 1955

Author

Professor Azim Nanji

Azim Nanji is currently Special Advisor to the Provost of the Aga Khan University, and a member of the Board of Directors of the Global Centre for Pluralism in Ottawa, a joint partnership between His Highness the Aga Khan and the Government of Canada. He has held many prestigious academic and administrative appointments, most recently as Senior Associate Director of the Abbasi Program in Islamic Studies at Stanford University, where he was also lecturer in the Department of Religious Studies. From 1998 to 2008, Professor Nanji served as Director of the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London.

Professor Nanji has published numerous books and articles on religion, Islam and Ismailism, including: The Nizari Ismaili Tradition (1976), The Muslim Almanac (1996), Mapping Islamic Studies (1997) and The Historical Atlas of Islam (with M. Ruthven) (2004) and The Dictionary of Islam (with Razia Nanji), Penguin 2008. In addition, he has contributed numerous shorter studies and articles in journals and collective volumes including The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Modern Islamic World, and A Companion to Ethics. He was the Associate Editor for the revised Second Edition of The Encyclopaedia of Religion.

Within the Aga Khan Development Network, he has served as a member of the task force for the Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations (AKU-ISMC) and Vice Chair of the Madrasa-based Early Childhood Education Programme in East Africa. He served as a member of the Steering Committee of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1998, 2001 and 2016.

Dr Farhad Daftary

Co-Director and Head of the Department of Academic Research and Publications

An authority in Shi'i studies, with special reference to its Ismaili tradition, Dr. Daftary has published and lectured widely in these fields of Islamic studies. In 2011 a Festschrift entitled Fortresses of the Intellect was produced to honour Dr. Daftary by a number of his colleagues and peers.

Berchem, Max van. “Epigraphie des Assassins de Syrie”, Journal Asiatique, 9 série, 9 (1897), pp. 453-501; reprinted in his Opera Minora. Geneva, 1978, vol. 1, pp. 453-501.

Bianquis, Thierry. Damas et la Syrie sous la domination Fatimide, 359-468/969-1076. Damascus, 1986-89. 2 vols.

Canard, Marius. “Fatimids”, in The Encyclopaedia of Islam (revised ed.), vol. 2, pp.850-862. Daftary, Farhad. The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge, 1990. Daftary, Farhad. The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Ismailis. London, 1994.

Daftary, Farhad. “The Ismailis and the Crusaders: History and Myth”, in Z.Hunyadi and J. Laszlovszky, ed. The Crusaders and the Military Orders. Budapest, 2001, pp. 21-41; reprinted in his Ismailis in Medieval Muslim Societies. London, 2005, pp. 149-170.

Daftary, Farhad. “Rashid al-Din Sinan”, in The Encyclopaedia of Islam (revised ed.), vol. 8, pp. 442-443.

Daftary, F. and J.H. Kramers. “Salamiyya”, in The Encyclopaedia of Islam (revised ed.), vol. 8, pp. 921-923.

Ghalib, Mustafa. The Ismailis of Syria. Beirut, 1970.

Halm, Heinz. “Les Fatimides à Salamya”, Revue des Etudes Islamiques, 54 (1986), pp. 133- 149.

Hodgson, Marshall G.S. “The Ismaili State” in The Cambridge History of Iran: Volume 5, The Saljuq and Mongol Periods, ed. J.A. Boyle, Cambridge, 1968, pp. 422-482.

Ibn al-Athir, ‘Izz al-Din Ali. al-Kamil fi’l-tarikh, ed. C.J. Tornberg. Leiden, 1851-76. 12 vols.

Ibn al-‘Adim, Kamal al-Din. Zubdat al-halab min tarikh Halab, ed. S. Dahan. Damascus, 1951-68. 3 vols.

Ibn Muyassar, Taj al-Din Muhammad. Akhbar Misr, ed. A.F. Sayyid. Cairo, 1981. Ibn al-Qalanisi, Hamza b. Asad. Dhayl tarikh Dimashq, ed. S. Z'Akkar. Damascus, 1983.

Joinville, Jean de. Memoirs of John Lord de Joinville, tr. Thomas Johnes. Hafod, 1807. 2 vols.

Lewis, Bernard. “Kamal al-Din’s Biography of Rasid al-Din Sinan”, Arabica, 13 (1966), pp. 225-267; reprinted in his Studies in Classical and Ottoman Islam. London, 1976, article X.

Lewis, Bernard. The Assassins. London, 1967.

Mirza, Nasseh. Syrian Ismailism. Richmond, Surrey, 1997.

Nanji, Azim. “Assassins” in the Encyclopaedia of Religion, vol. 1, pp. 469-471.

Nasir-i Khursraw. Book of Travels (Safarnama), ed. and tr. W. M. Thackston Jr. Costa Mesa, CA, 2001.

Nasr, S. Hossein. ed. Ismaili Contributions to Islamic Culture. Tehran, 1977. Willey, Peter. Eagle’s Nest: The Ismaili Castles of Iran and Syria. London, 2005.

William of Tyre. A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, tr. E.A. Babcock and A.C. Krey. New York, 1943. 2 vols.

The use of materials published on the Institute of Ismaili Studies website indicates an acceptance of the Institute of Ismaili Studies’ Conditions of Use. Each copy of the article must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed by each transmission. For all published work, it is best to assume you should ask both the original authors and the publishers for permission to (re)use information and always credit the authors and source of the information.

© 2007 The Aga Khan Trust for Culture

© 2007 The Institute of Ismaili Studies